|

First published December 1, 2020

Last updated October 15, 2025 The Douay-Rheims Bible In another article I reviewed the English Standard Version, Catholic Edition (ESV-CE) of the Bible where I was happy to report that the ESV-CE is an accurate translation, and is available in electronic and audio editions. Another Catholic Bible that checks all those boxes is the Douay-Rheims Bible. The Latin Vulgate The Douay-Rheims Bible was produced in the late 16th and early 17th century, and revised in the mid 18th century. It is an English translation of Saint Jerome's 4th century Latin Vulgate. Any discussion of the Douay-Rheims Bible must include the Latin Vulgate. The Latin Vulgate is based on Older Hebrew manuscripts of the Old Testament The Old Testament was originally written in Hebrew (with a few parts in Aramaic). Most English Old Testaments are translated from the Hebrew Masoretic text which was produced between the 7th and 10th centuries A.D. The earliest extant manuscript of the Masoretic text is from the 9th century A.D. The Masoretic Hebrew text does not contain the Deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament.

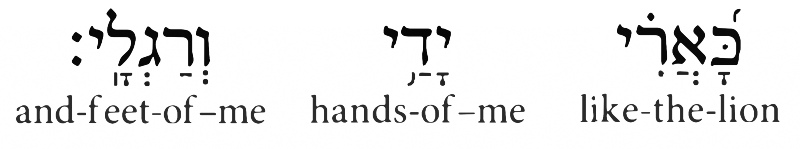

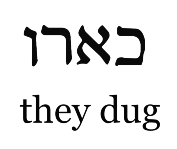

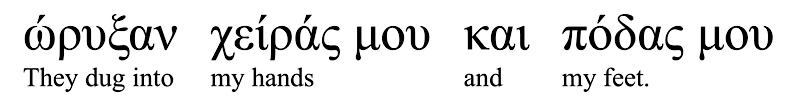

That older Hebrew text was later uncovered in the 20th century when it was found in manuscripts among the Dead Sea Scrolls which are a thousand years older than the oldest extant Masoretic text manuscript. Every book in the Old Testament except Esther is represented in the Dead Sea Scrolls, including the Deuterocanonical books. A great article, Masoretic Text vs. Original Hebrew has more about the differences between the two texts. This older Hebrew text only exists in fragments today, but the parts that do exist can be read in English at the web site Dead Sea Scrolls Bible Translations. There is also a book available called The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible The Septuagint and the Syriac both correspond to this earlier Hebrew text. The Septuagint is a Greek translation the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C. and the Syriac is an Aramaic version from the 5th century A.D. The Masoretic text was produced after the Christian Church was established, and some parts of it have a subtle anti-Christian bias. The Masoretes were Jewish scribe-scholars, and were naturally inclined to reject any textual options that would lend credibility to the Christian understanding of the Messiah, such as prophecies. One famous example is Psalm 22 (Psalm 21 in some Bibles) which is regarded as prophecy concerning the crucifixion of Christ, particularly verse 16 which says they pierced my hands and feet. Most Masoretic text manuscripts have like the lion, my hands and my feet which eliminates the prophetic wording. (Hebrew reads from right to left, and the Masoretic text has tiny markings to indicate vowels.)  Two Dead Sea Scrolls contain Psalm 22, and they both read: they pierced (or dug) my hands and feet. The difference between like the lion and they dug is merely one elongated stroke of one character.  Most English Bible versions are forced to depart from the Masoretic Text at this point and delegate it to a footnote. Here are four popular versions along with their footnotes:

However, the Septuagint agrees with the Dead Sea Scrolls.  These Orthodox Bible versions are translated from the Septuagint:

As you can see below, the Latin Vulgate also agrees with the Hebrew text of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Douay-Rheims Version is translated from the Latin Vulgate:

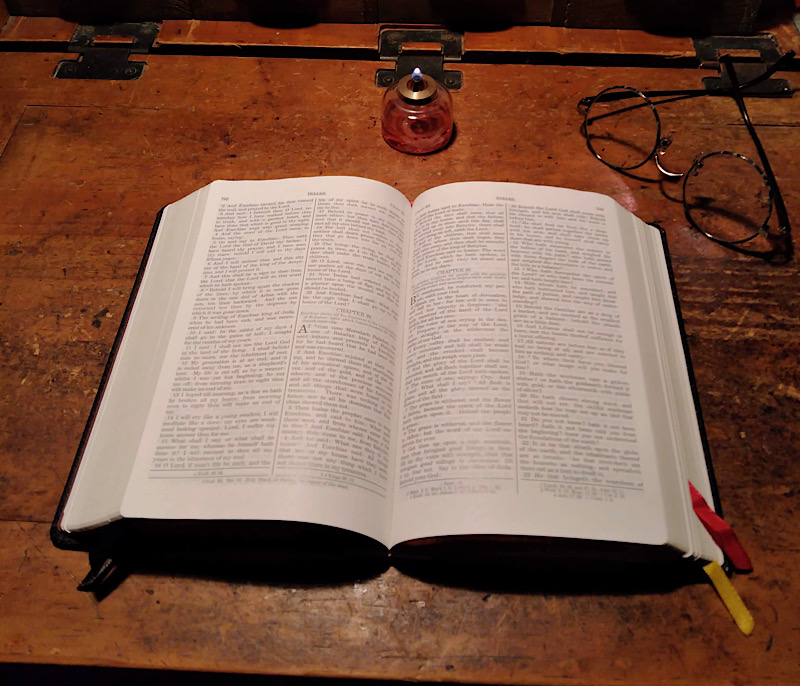

Psalm 22 is so important to Christians, that most Protestant English Bibles had to abandon the Masoretic text in this one spot. In other similar cases they just go with the Masoretic text. The differences between the two Hebrew texts are usually insignificant, but I would trust the older Hebrew text over the Masoretic text. A commentary or footnote will sometimes say that a phrase in the Douay-Rheims Bible is not found in the Hebrew text but is in the Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate. There is no need to lose confidence in the Douay-Rheims because the Hebrew they are referring to is the Masoretic text, which is still the only complete Hebrew text of the Old Testament available today. The phrase may well have been included in the ancient Hebrew text, which would explain why it appears in the Septuagint or Latin Vulgate. The Latin Vulgate is based on Older Greek manuscripts of the New Testament The New Testament was originally written in Greek (although some have claimed that parts may have been originally written in Aramaic and translated at a very early stage to Greek). Some of the New Testament Greek manuscripts available to Saint Jerome came from the second century and would have been early copies of the original autograph manuscripts. It's worth noting that the original manuscript of the Gospel of John was supposedly still preserved in the Church in Ephesus at that time, so Jerome who was doing the translation project with the full support of Pope Damasus who had requested the project may have been able to translate directly from at least one autograph. Some have argued that although Saint Jerome had access to early Bible manuscripts, he did not have access to the thousands of manuscripts which have been discovered since Jerome's time, and which are available to today's translators. One particular web article called Uncomfortable Facts About The Douay-Rheims pushes this idea. What that article fails to acknowledge is that the thousands of Greek manuscripts we now have were made much later than the ones Saint Jerome used, and were often produced in large numbers as one person read a manuscript out loud and scribes wrote down what they heard. How could these newer mass-produced manuscripts be of more value than the ancient manuscripts that Saint Jerome used? The article also goes on to say that Saint Jerome lacked the critical apparatus we have for sorting through textual variants. Again, Jerome was working with very early manuscripts which were produced at a time before all those textual variants started to appear. Concerning Old Testament Hebrew manuscripts, we have already established above that modern Bible translators can't possibly have access to Hebrew manuscripts that are older than what Jerome used because they simply don't exist outside the fragments in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Closer to the original time Saint Jerome was fluent in Greek and Latin and knew Hebrew and Aramaic as well. He was born around 342 A.D. and knew these languages in the form that they existed back then. This is especially true for the New Testament which was written only a few centuries earlier in Greek. Saint Jerome did not need dictionaries or grammars. He did not have to mechanically translate the same word into Latin the same way every time, but could choose the best word for the context. If a few centuries seems like a long time, remember that this is about the same span of time that separates us from Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence. The Latin Vulgate in English One of the biggest arguments you will hear against using the Douay-Rheims Version is the fact that it is a translation from the Latin Vulgate rather than the original Hebrew and Greek texts. On the surface, this would appear to be a deal breaker because there is usually more than one way to translate a word or phrase; there can be several options, and sometimes it can come down to a judgment call. This could move the nuance of the translation away from the intention of the original, and would be exacerbated if the translation undergoes a subsequent translation. The Douay-Rheims translators had the option of translating directly from the Hebrew and Greek texts which were available to them but were wary of these texts because they contained many variants caused by copyist errors. They said that these manuscripts were not as pure as the Latin Vulgate. Instead of translating directly from Hebrew and Greek texts, they made an English translation of the Latin Vulgate and "diligently compared" their work with the Hebrew and Greek to make sure their English was also aligned with these underlying languages. This made the Latin Vulgate transparent, so the Douay-Rheims is as much a translation of the original Hebrew and Greek as it is of the Latin, and not merely a "translation of a translation" as some claim. In the case of differences between the Latin and Hebrew or Greek texts, the translators sided with the Latin, believing it represented a more ancient and pure Hebrew and Greek text. Word-for-word translation The Douay-Rheims version is a word-for-word (a.k.a. formal equivalence) translation. Like other formal equivalence translations, this version has italics for words that do not appear in the first language but are needed to get the same meaning in English. Granted, the first language in the Douay-Rheims is Latin, but so far I have found that the italics correspond with missing words in Greek and Hebrew as well. In the Douay-Rheims, quotes from the Old Testament are also in italics, which is very helpful and cause no confusion because they are phrases rather than isolated words, and are preceded by a small letter indicating there is a cross reference in the footnotes. Also, in the Greek New Testament, the authors would often use the historical present tense which livens up the narrative. We still use it today, particularly in funny stories, such as two men walk into a bar. One example is in Matthew 3:1 which reads, And in those days cometh John the Baptist preaching in the desert of Judea. The regular present tense came would have fit the sentence better, and modern versions convert these to the regular past tense without telling you. The producers of the NASB to their credit insert an asterisk to alert the reader that the original Greek was in the historical present tense. But the Douay-Rheims translates the verb just as it is, in the historical present tense, even though the sentence may sound awkward. The King James Bible also does this. This faithfulness to the original languages which results in awkward English makes the Douay-Rheims Bible feel like a grown-up Bible. A few problem passages Whenever anyone criticizes the Douay-Rheims Bible, it's just a matter of time before 1 Kings 13:1 comes up (1 Samuel 13:1 in Protestant Bibles). It says in the Douay-Rheims, Saul was a child of one year when he began to reign, and he reigned two years over Israel. Anyone who has read the story of King Saul in the Bible will know that he was not one year old when he began to reign, and he apparently reigned for over forty years. This problem is not just with the Douay-Rheims, but goes all the way back to the Hebrew text where crucial numbers are missing but are implied. The Douay-Rheims reflects the problematic Hebrew text. Other English translations conveniently add appropriate numbers or shift the meaning of the verse so that it makes sense. The translators of the Douay-Rheims Version did not consider these options and worked according to their strict translation principles so that the problematic parts in the Hebrew text were brought directly over into English. I'd rather be confronted with such a challenge than be spoon-fed someone else's interpretation. Another difficult passage is Exodus 6:2-3. In the Douay-Rheims it says that God's proper name is ADONAI which is the Hebrew word for Lord. But the actual Hebrew name in this case is the Tetragrammaton YHWH. Most other English Bibles translate this name as Yahweh, Jehovah or LORD (in all caps). There is a footnote in the Douay-Rheims Bible explaining why they translated the name this way (so make sure you get an edition with the footnotes). The Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate both opted for the word for Lord (Kurios and Dominus respectively), so the Douay-Rheims does the same, but uses the Hebrew word ADONAI for the Latin word Dominus, and the result is awkward and misleading. Speaking of which, I do prefer some kind of clue that signals when the Tetragrammaton appears, such as the all caps LORD, and I miss that when I read the Douay-Rheims. Such passages serve to remind us that the Douay-Rheims is not perfect. No English Bible is perfect. But I believe the Douay-Rheims is generally more accurate and faithful to the original text than other English Bibles. It's a good idea to have some reference source or commentary (even if it's just the Douay-Rheims footnotes), or access to more than one version for comparison. When you come across a passage which could have been clearer or more closely translated, just write your preferred wording in the margin so that you will have an even more perfect English translation of the Bible. My Bibles all have such notes in the margins. Older English There is one challenge with the Douay-Rheims Bible which has nothing to do with the underlying language texts, but rather with the constant evolution of the English language. Some English words have changed their meaning over the years, and some words are no longer used. This is not as big an issue as some people make it to be; such unfamiliar words are few and far between, are often made clear by the context, and are sometimes explained in the footnotes (again, so you need an edition that has the footnotes!). As you read through the Bible, simply look up the unfamiliar words and write the definitions in the margins. Then the Douay-Rheims Bible will be as familiar as any modern translation. The second time you read through it, all the speed bumps will have been removed, and your knowledge of English will also have increased. The words of the Douay-Rheims Bible are from an era when the English language was more beautiful. While it might not be everybody's cup of tea, the words are arguably more beautiful and dignified than modern English translations. And that older form of English is more precise than modern English. For example, the pronouns thou, thee, thy and thine are singular while you, ye, your and yours are plural. Modern English has lost that distinction unless y'all hail from the south. This may seem like a trivial distinction, but sometimes doctrine hinges upon it. For example, there were times when Jesus was referring to the twelve and there were times when he was referring exclusively to Peter, but you would never know that in a modern English Bible unless the notes gave you a clue. Cultural differences A lot of the language speed bumps of the Douay-Rheims Bible has nothing to do with the state of the English language as it existed a few centuries ago. Since it is a word-for-word translation, phrases which came from ancient cultures are brought directly into the English Bible. For example, when the angel asked Hagar the mother of Ishmael where she was going after she had run away from Sarah, she replied in Genesis 16:8, I flee from the face of Sarai, my mistress. Most modern translations omit the reference to the face. Even the very literal NASB changes it to presence. The original phrase is easy enough to grasp in our current culture, and doesn't need to be omitted. I like to be reminded that I am reading a document which was written in the context of an ancient culture. Different spellings In addition to unfamiliar words, you will come across unfamiliar spellings in the Douay-Rheims for old familiar names, particularly in the Old Testament. For example Noah becomes Noe, Hosea becomes Osee, and Haggai beomes Aggeus. Apparently these reflect the Latin versions of these names, and it can really be a distraction for Protestant converts to the Catholic Church who are accustomed to different spellings. No English Bible gives the exact equivalent of biblical names. For example, Yakob would be much more authentic than James, and Yeshua would be closer to the original than Joshua or Jesus. It's simply a matter of what you are accustomed to, and you might get used to them. You could also expand your frame of reference to include alternate pronunciations for many Biblical names. Perhaps you can take comfort in the fact that these different spellings can be closer to the original pronunciation. When reading the Douay-Rheims Bible, you cannot for a moment escape the sense you are reading an ancient document -- which you are. But if the unfamiliar spellings are a big obstacle (and I admit they are for me) you can fix the problem by listening to the Douay-Rheims audio Bible recorded by Steve Webb as you read the Bible. Steve pronounces the names as they appear in modern Bibles. I have written more about the audio Bible below. Different Psalm numbering Those who come to the Douay-Rheims Bible from other versions including modern Catholic translations will notice the Psalm numbers don't match. That's because the numbering system comes from the Greek Septuagint rather than the Hebrew Masoretic text. Some other Bibles also use this numbering system, particularly Bibles used by the Orthodox churches. If you are familiar with the Psalms and their Hebrew numbering, this will take a little adjustment on your part. Here's a little chart I made that will serve as a quick reference when you want to know which Psalm in the other Bibles corresponds to the one you are reading in the Douay-Rheims. It comes three on a sheet, and you can cut them out and use them as bookmarks. Stable When I was a young Protestant I memorized over 500 Bible verses plus the entire first letter of John from the New American Standard Bible (NASB). Little did I know that this Bible would would be replaced in 1995 by an updated edition using the same name, and that the 1995 edition would be replaced by a 2020 edition. It goes without saying that as Bible translations come and go, I have lost my appetite for Bible memorization. The Douay-Rheims has existed in its present form since the mid 18th century and is not likely to be revised. Modern translations are modified to conform the English to current usage, and also to reflect modern manuscript discoveries. Those discoveries supposedly bring the Bible text more in line with the original texts which no longer exist, but since the Douay-Rheims Bible was based on ancient manuscripts already, so there is no need to do this. The Douay-Rheims Bible is immune from the constant revision merry-go-round that affects new Bible versions, so I may start memorizing verses again. When Bishop Richard Challoner revised the Douay-Rheims Bible in the mid 1700's, one of his concerns was that Catholics at the time were reading the Protestant King James Version of 1611 which had become very popular. He borrowed heavily from that translation, which is considered a bad thing in the eyes of some Catholics, and a good thing in the eyes of some Protestant converts to the Catholic Church. Challoner himself was a former Protestant who was very familiar with the beauty and strengths of the King James Version. If there were English phrases in the KJV which were accurately translated and faithful to Catholic teaching, why should Challoner deliberately come up with alternate English phrases just to keep his revision different from the KJV? That's what Bible translators must do today because of copyright laws; they have to do all sorts of acrobatics just to avoid the exact wording of existing English Bibles -- and there are over 450 English versions of the Bible now. The resulting translation choices are probably not be the best because the best choices were already used in previous English translations. Bishop Challoner did his work back when there were not all these English Bibles versions to contend with, and he was not hindered by copyright laws; he was free to choose the best English words possible, even if they first appeared in the King James Version. For those who want to read the 17th century Douay-Rheims Bible before it was revised by Bishop Challoner, there is an edition which simply modernizes the spelling of the older edition and keeps the contents the same. It is called the New Douay-Rheims Bible and was produced by John Litteral. Since only the spelling has been modernized, and the contents have not been changed, this Bible apparently enjoys the same official approval of the Catholic Church as the original 1609 Douay-Rheims Bible. Both this older edition and the Challoner edition are approved by the Catholic Church Please note that this work is not the same as the Protestant publication called The New Douai Rheims Bible which omits the Deuterocanonical books and original notes, and is not approved by the Catholic Church. Faithful For over three hundred years, the Douay-Rheims was the definitive traditional Catholic Bible in English. Pope Pius XII declared that its underlying text, the Latin Vulgate was free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals. This is the Bible that has full of grace in Luke 1:28 while most of the other translations have favored or highly favored. And the angel being come in, said unto her: This is one of several Bible passages which traditional Catholics will check when evaluating English Catholic Bibles. I called them Catholic "Hot Spots" in my article about the ESV-CE. I became aware of such passages several years ago when I read an e-book called Which Bible Should You Read? which promotes the Douay-Rheims Bible. It was written by Thomas A. Nelson, founder of TAN Book and Publishers. I tried to find it recently, but couldn't find it on their web site (maybe it had something to do with their acquisition by Saint Benedict Press). After searching the web for a long time, I finally found a copy of the PDF on a different website and have decided to make available here as well so that it won't completely vanish from the web. It is definitely an encouraging publication for anyone who prefers the Douay-Rheims Bible. The Douay-Rheims Bible remains the Bible of choice for many traditional Catholics. Beautiful The Douay-Rheims Bible comes in many editions from several publishers including beautiful leather editions with gold-edge pages. The Bible in the photo below is a black leather Pocket size edition

I also have their pocket New Testament

Some editions of the Douay-Rheims Bible are photographic reproductions of older editions; the pages were scanned and re-printed, but there are a few editions of the Douay-Rheims Bible which have been newly typeset for a crisp, clean appearance which is more readable. These Baronius Press Bibles were done this way. Others include Saint Benedict Press I have inserted Amazon links to some of these products because it serves as a sort of a tip jar for me at no extra cost to the reader. Of course, you can also get these Bibles from other vendors or directly from the publishers, which is a good idea when Amazon's supply of these Bibles occasionally gets low and their prices suddenly go through the roof. Here are links to the three publishers mentioned above: If your local book store has the book you're looking for, buy it there and show them your support. Audio

You can find it all over the internet, and you can listen to it on YouTube. So the Douay-Rhems Bible is accessible to those who have visual impairments and must listen to the Bible rather than read it. I like to listen to the Douay-Rheims Audio Bible while I'm doing the supper dishes; I've done this for several years now, and can go through the entire Bible twice in a year depending on how many dishes I have to wash. To my surprise I've discovered that most of the obstacles one might have when trying to read older English mysteriously melt away when you are simply listening to it, especially if it is read well by a professional. One reason is that Steve Webb fixed the older names which were based on their Latin translations, and pronounced them as they appear in current English Bibles. This is an amazing feature, and I'm so glad he made the bold decision to so this. If you are having problems connecting with the older names, then I recommend listening to this audio Bible as you read the Douay-Rheims Bible. The difference is like night and day. It also makes the reading time more enjoyable. It's easier to stay focused and fight distractions when the Bible is coming to you through both your eyes and ears. And even if you take your eyes off the text for a moment, the reading continues uninterrupted. This audio Bible is offered as regular MP3 audio files and also as MP4 video files which display the text as you listen to it. If you already have an digital edition of the Douay-Rheims Bible and your device has a split screen option, you can have the Bible open in one screen and the audio Bible open in the other screen. I've written more on this feature below about Digital options. Digital options The Douay-Rheims Bible is a great choice for those who want to study a very accurate Catholic Bible on a computer. Because it's so old and in the public domain, you can get digital editions for free. Here are some websites which have the Douay-Rheims Bible online:

You can also use a smartphone to view these. Then you will always have a Bible with you, and you can read your Bible in the dark. You can also make the font bigger if you forgot your glasses. Of course, the more screen space you have, the better the experience. If you were looking for a good reason to justify investing in a tablet, maybe now you have it. As I mentioned above, the biggest problem many people have with the Douay-Rheims Bible is its English. Many English words have a different meaning today, or are no longer in use. The best solution is to have a Bible that is linked to a dictionary so that all you have to do is touch a word to get its definition. I think this ability to just touch a word and get more information is the biggest advantage that digital resources have over paper ones. No more juggling several books at once. I have the Verbum Catholic Bible Study app on my tablets and my phone. This is apparently the best Bible study app available for Catholics and is compatible with practically every computer, tablet and phone, so you can sync your data across all your devices when they are connected to the internet. Verbum has several different packages which vary by the number of books in their library; you can get over 3,000 books in one package. These range in price from around 250 dollars all the way up to over 4,000 dollars. But for those of us who can't afford these apps and only want a Bible and a few resources, there is also a free version of the Verbum app which is called Version 8 Basic. It gives you access to a small collection of free books including the Douay-Rheims Bible. The free Verbum app is not easy to find in the Verbum website itself, and you may have better luck in the Apple app store or Google Play. The Verbum Douay-Rheims Bible doesn't have italicized words, but it does have a pop-up dictionary. You also have access to several commentaries. The Verbum app lets you underline and highlight verses and type in your own notes, so you no longer have to carry around a bunch of highlighter pens or colored pencils. It also lets you take advantage of the split screen option available in some tablets so that you can have a different resource open in the second window. You can also scroll left or right to go directly to other resources within the Verbum window. If you click on the three dots in the upper right hand corner and go to their "Exegetical Guide" you can see the passage in Hebrew or Greek with the pronunciation and definition of each word. Yes, this is part of the free package. If you are listening to the audio Bible in the second window, you can adjust the speed of the audio Bible according to the content, and make it go a little faster when there are long lists of names or numbers, or a little slower when there is a lot of teaching packed in the text which requires more time to digest. If you search the web, you will even find tablet covers that look like Bibles so you might not get funny looks if you use a digital Bible in Church. Just make sure you've disabled incoming phone calls and other distractions. Haydock's Bible Commentary Speaking free resources, I have to mention Haydock's Bible Commentary. It gives you different variant readings found in the Hebrew and Greek, explains difficult passages and tells you how the Church Fathers and Doctors of the Church interpreted them. If you are using the Douay-Rheims, then you'll want to have Haydock close at hand. The Verbum app has Haydock's Bible Commentary for free, and you can have it in a second window on a tablet, and link it to the Bible in the first window, so wherever you are in the Bible, the commentary will be at the same place. You can also use Haydock's Commentary for free online at several websites such as Haydock Commentary Online where the Commentary is in the left column with the Douay-Rheims Bible in the right column, complete with italics and cross references. A very similar web site with the commentary on the left and Bible on the right is at the Web Archive. Haydock's Commentary can also be found by itself without the Bible text at e-Catholic 2000. It is also available at the Bible Hub. If you prefer a real physical book and have some money to spare, you can get the entire Douay Rheims Bible with Haydock's Commentary New things and old Speaking of physical books, I'm sure a lot of folks wouldn't even think of replacing their beautiful Douay-Rheims Bibles with electronic devices. One big advantage of a physical Bible is the ability to freely flip back and forth through the pages when you are looking for something. I also prefer bringing a real Bible to church. My tablets have disappointed me when I was in a situation where there was no power or WiFi, but my Bible has always been a faithful friend. Still, it's nice to have a digital Bible and all those resources when I only have access to a phone or tablet. Read the Bible in a year

If you would like to modify the charts, I've also included the excel files. I actually created these charts in Google Sheets and exported them as Excel files, so the Excel files may look a little strange, but I hope they are still useable or at least fixable. You can print these out and take a glue stick that has restickable, repositionable glue and glue a strip down the back along one edge to make it a huge Post-it. Then stick them onto blank pages in the back of your Bible. I designed these to be printed on A4 size paper. You may have to fiddle with the paper size settings if you are using a different size paper. You can also download the PDF to your tablet, make a duplicate and check off the chapters with a stylus. You can find more charts and free resources at my Resources page Beautiful Breviary If you are drawn to dignified traditional language, you are probably not so thrilled about modern English breviaries. However, there are a few breviaries which use the Douay-Rheims Version, such as The Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary I have written more about the Little Office in a separate article called The Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary for those who love the Douay-Rheims Bible. Final thoughts Speaking of checking boxes, other Catholic Bibles do check some of the boxes I mentioned at the beginning of this article, but not all of them. For example, the Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (RSV-CE) comes in a digital edition and the New Testament is available in audio form, but not the Old Testament. The New American Bible Revised Edition (NABRE) is another Catholic Bible which is available in digital and audio form, but that translation is not very accurate and has troubling footnotes which go against Catholic Tradition and can even undermine one's faith in the Bible. As for the ESV-CE, I have studied and annotated my copy from cover to cover several times and can say with confidence that it is an excellent Catholic Bible, especially for those who prefer modern English. The ESV is one of the best and most accurate Protestant translations on the market, and the ESV-CE is very appreciated by Catholics like me who converted from Protestantism. I have been reading the Bible for over fifty years (most of those years as a Protestant) and have read through half a dozen Bible versions, some of them many times over. I'm not a Douay-Rheims onlyist, but I am very happy with the Douay-Rheims Version, and that excitement has compelled me to write this article. | |||||||||||||