|

First published October 2012 Last modified December 2019

Kirishitan Sites in Tokyo

What is a Kirishitan? Kirishitan (sometimes spelled Kirish'tan) is simply the old Japanese word for Christian. It is currently used to designate the early Christians of Japan from the 14th century until the 19th century, as well as their direct descendants who still exist, and are often called Kakure Kirishitan or "hidden Christians." As for pronunciation, kee-leesh-tan is close enough. The Japanese "a" sound rhymes with "swan" (not "cat"). Today Japanese Christians are called Kurisuchan (koo-lees-chan). The name Kirishitan is usually written in either katakana or hiragana characters, but it originally appeared in the form of kanji characters.

So the pair of kanji for KIRI was changed to a single kanji with a different meaning. This kanji was the character for cutting, and when combined with second kanji which can mean branch, it conjures up the image of cutting off branches. This was intended as a cruel insult to Kirishitans who were often punished by severing body parts including limbs, and were often executed by beheading. (By the way, whenever Japanese names appear in this article, the family name will appear first, followed by the individual's name, according to Japanese custom). Kirishitans in Tokyo The largest Kirishitan populations were in Kyushu in the southwest part of Japan, and today the great majority of Kirishitan sites are located there. By comparison Tokyo (called Edo in those days) had a much smaller Kirishitan presence, and has only a few Kirishitan sites. Several of the Kirishitan incidents took place in Edo because it was the military and political capital of Japan and prisoners were brought there after they were arrested in other parts of Japan. I have been able to track down lots of information from various sources including old out of print library books in Tokyo. Some of these books had horizontal lines of Japanese text running from right to left which indicates they were published before World War II. Tokyo has changed drastically since then, which makes it very difficult to track down these sites based on the descriptions. Even old photos are no longer helpful as buildings and entire neighborhoods have been demolished and replaced by newer office buildings and shopping complexes in ever-changing Tokyo.

I have read that there are more unmarked sites connected to Kirishitan stories around Tokyo, and this article continues to grow as new archaeological discoveries appear in the news. Let me start from the beginning and in chronological order weave some of the stories of the Kirishitans into the descriptions of the sites which I have found. Francis Xavier was the first Christian missionary to arrive in Japan 1. Xavier had met a Japanese man named Anjiro (or Yajiro) in Portuguese Malacca (part of Malaysia) in December 1547. Anjiro had heard of Xavier and traveled to Malacca to find him. He told Xavier about this amazing country in the Far East. Francis Xavier arrived in Kagoshima on the southern island of Kyushu on August 15, 1549. He was accompanied by two missionaries and Anjiro (who became the first Japanese Christian). Xavier did not come as far north as Tokyo which was called Edo in those days. He was only in Japan for a little over two years and spent his entire time in the southern part of Japan with only one visit to Kyoto the old capital of Japan in hopes of meeting and converting the emperor.

This new strategy proved very successful. During his short time in Japan, Xavier baptized some 760 Japanese including many influential military rulers. Francis Xavier had great hope for this nation. He wrote: Japan is the only country yet discovered in these regions where there is hope of Christianity permanently taking root. Even with all their trials, it was apparently an exciting time for Francis Xavier and his fellow missionaries as the Japanese eagerly embraced the gospel in ever increasing numbers. According to reports and an investigation by Church authorities, Xavier's ministry was even accompanied by extraordinary miracles including raising the dead. Although there were many eye-witness testimonies by Xavier's co-workers and converts, he himself was silent on the matter. But dark clouds were on the horizon. Francis Xavier was in charge of all the missionary work in the Far East, and his other duties forced him to leave Japan for a while -- with every intention of returning later with more missionaries. He left Oita (called Funai at the time) at the end of 1551. A year later, hoping to evangelize China, Xavier arrived on Shangchuan Island, 14 kilometers off the coast of the mainland. He had paid a large sum of money to a Chinese merchant to bring him to the mainland by boat, but the boat never arrived, and Xavier died of a fever on December 3, 1552. His two companions, Fr. Cosme De Torres and Brother Juan Fernandez remained in Japan and sacrificially gave their lives to the work for the next sixteen years, overseeing the Church in Japan which spread as more missionaries arrived, some which had been sent by Xavier himself before he died. His successor in charge of all the missions, Fr. Alexander Valignano wrote: Of all the nations that I have ever visited, Japan is the most appropriate nation to receive God's salvation.

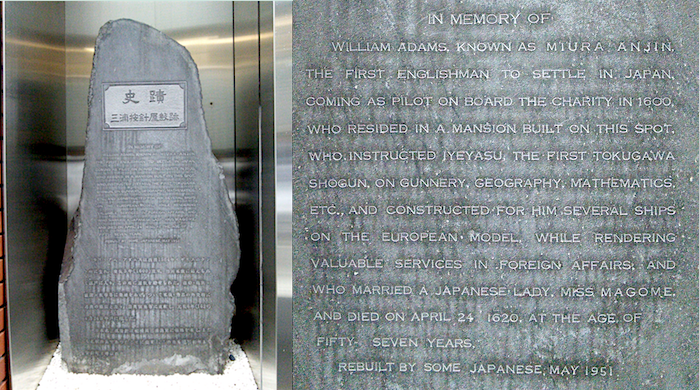

The Church continued to expand in southern Japan without hindrance for almost fifty years, especially during the rule of Oda Nobunaga who welcomed and protected the foreign missionaries. Then in 1597 Christianity was forbidden by Hideyoshi Toyotomi who was the military ruler of Japan after Nobunaga's death. The priests scattered throughout Japan and continued their mission secretly. Persecution and martyrdom became a reality and yet the Church continued to grow. The Church eventually reached Edo (Tokyo) where Tokugawa Ieyasu had based his operations and built his impressive castle which would become the military capital of Japan for over two and a half centuries during the Edo era. Although Christianity had been officially outlawed by Hideyoshi Toyotomi, Tokugawa Ieyasu did not enforce this ban at first. He even gave permission to a Spanish Franciscan missionary from Kyoto, Fr. Geronimo de Jesus Castro, to begin evangelistic work in Edo. Although the missionary work in southern and central Japan had been initially done by Jesuit priests, in Tokyo and northern Japan the work was begun by Francisan and Dominican missionaries. Around that time one of Tokugawa Ieyasu's advisors was the Englishman William Adams (also known by his Japanese name Miura Anjin) who opposed the work of the Catholic missionaries. Adams had a mansion in Edo, and there is a memorial stone to mark the spot in the Nihonbashi area now.

Adams married a Japanese woman who had a Catholic sister and brother in law, and may have been a Catholic herself. Incidentally, Adams already had a wife and children in England. The main character John Blackthorne in the novel Shogun by James Clavell was loosely based on the life of William Adams. Site 1.

In 1599 Fr. Geronimo built a chapel in the area of Hatchobori and Nihonbashi with the full permission of Tokugawa Ieyasu. This chapel was the first Christian church in Edo and was called ROZARIO NO GENKOU SEI MARIA SEIDO (Church of Queen Holy Mary of the Rosary). In 1601 Fr. Geronimo had an audience with Ieyasu. This was after the decisive battle of Sekigahara of 1600 which paved the way for Ieyasu to become shogun (military commander-in-chief of Japan) in 1603. He presented the soon-to-be shogun many gifts (including tobacco seeds which later had a different sort of impact on Japan's culture) and apparently won his favor. Ieyasu then sent Fr. Geronimo to the Philippines as his ambassador. He returned to Japan and died in Kyoto in 1601. The church building became the base for further evangelism in Edo and the surrounding areas under the leadership of Spanish Franciscan, Fr. Luis Sotelo who carried on the work after Fr. Geronimo's death. Sotelo was a powerful evangelist and his preaching was accompanied by miracles such as healing. Soon, the number of Kirishitans in Edo reached around 3,000.

Among those who experienced miraculous healings was the concubine of Date (pronounced DA-TEH) Masamune, a powerful Daimyo (feudal lord) who controlled the territory in northern Japan and founded the city of Sendai. Sotelo's powerful preaching was successful in persuading Date himself to become a believer, who declared that he would have been baptized if it weren't for his ambition to become Shogun (military dictator) of Japan. He knew that identifying with Christianity would prevent him from being appointed by the Emperor who was recognized as the head of the Shinto religion and even considered a living Shinto deity. Date resolved to worship God privately, and determined to compel all the people in his domain to be baptized instead. However, Sotelo convinced him that forced baptisms were not a good idea. It is said, however, that Date's daughter was later baptized. Then the Tokugawa Shoguns turned against Christianity and worked hard to eradicate it. In 1612 Christianity was banned from Edo. In 1612 or 1613 Tokugawa Hidetada, son of Ieyasu, destroyed the chapel -- 14 years after it had been constructed, and Luis Sotelo was whisked away by Date Masamune to Sendai where he would be safe. Today the exact location of that chapel is unknown. Site 2.

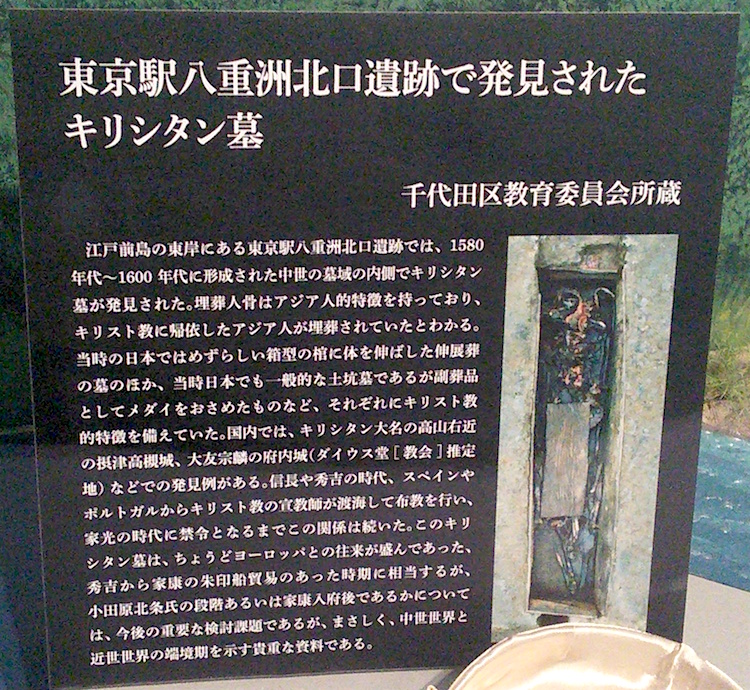

This graveyard was from the period between 1580 and 1600, and had a European style wood coffin with the body laid out horizontally, which was very unusual in Edo where the practice of cremation -- associated with Buddhism at the time -- was prevalent. In the Buddhist tradition, bodies were placed in an upright sitting position with the legs drawn up and the knees touching the chest in a wooden container resembling a barrel or tub which was then burned. The skeletal remains had Asian features which indicates it was not a European missionary. There was also a Christian medal and some rosary beads in the coffin. Today there is not so much as a plaque to indicate the exact location of this discovery. But the medal and rosary beads plus a photo of the coffin are in a permanent exhibition at the Hibiya Library in Hibiya Park not far from the burial site (and one would hope that somebody gave the remains a decent Christian burial in a new location). I visited the library and took photos of the display.

The description says that the medal has an image which could be either Christ or Mary along with the inscription "Immaculate Holy Mother" (which makes it clear that this is an image of Mary). Both the medal and beads are very old and the lighting was not so bright, so it was impossible to make out any details in the display case, or take a decent photo with my simple camera. So here are photos I found on the internet which show more details.

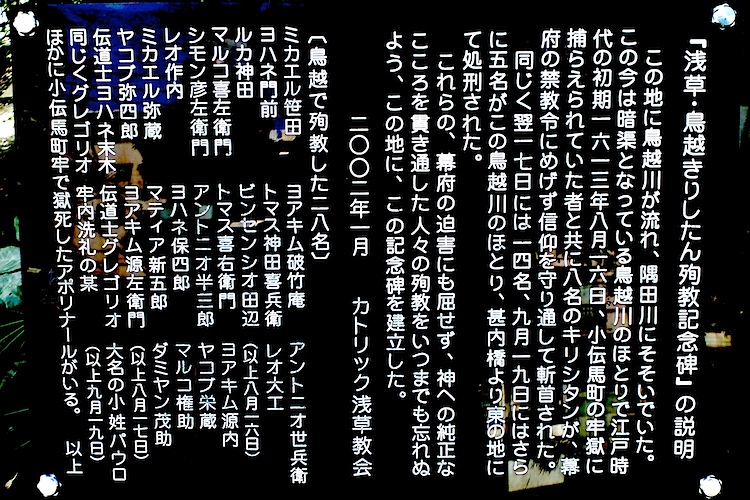

This burial site is near Tokyo Station and is also in the general Nihonbashi/Hatchobori area where the first Christian church in Edo ROZARIO NO GENKOU SEI MARIA SEIDO was was said to have been constructed, and one could imagine that Christians -- especially if they had been disowned by their own families -- would want to be buried near the church building as was the custom in Europe. At the very least, this church wasn't far away and we can assume that the Kirishitan who was buried here was associated with it since there was no other church in Edo. A second church in Edo Anyway, back up north in Sendai, Fr. Luis Sotelo was not content to stay in hiding under the protection of Date Masamune while the Christians in Edo were deprived of a church and their priest. So he soon returned with the goal of building a new church. Understanding the futility -- and danger -- of approaching the government for permission to build a new church to replace the one it had just destroyed, Fr. Sotelo went ahead and built a new chapel -- just a simple hut -- which would serve the Christians in Edo and serve as missionary headquarters. It was located about two kilometers away to the north in the Asakusa-Torigoe area, on the grounds of a leper hospital which was run by Kirishitans. The new church was completed on May 12, 1613 but was soon discovered by the authorities. This lead to the arrest of twenty seven Kirishitans who were thrown into Kodenmacho prison and then executed at the Asakusa-Torigoe execution grounds in three groups on August 16, 17, and September 19 of that year. Fr. Sotelo was also arrested and put into the same prison where he awaited his own execution but was later released to Date Masamune who interceded on his behalf. Date once again took the priest up north to Sendai. It was at this time that Date decided to send a diplomatic mission to Spain and Rome via Mexico in hopes of procuring a trade agreement, and also to invite many more missionaries to come to his domain in northern Japan. He sent Sotelo as an interpreter and liaison (and probably for his own safety after his zeal for evangelism in Edo had nearly gotten him killed). He had a ship specially built by Japanese ship builders who had acquired their knowledge and expertise from William Adams. The ship was called San Juan Bautista (Saint John the Baptist),

In Europe Hasekura was surrounded by Christians and Christian culture, and soon became a believer himself. He was baptized in Madrid along with other Japanese crew members. He also met Pope Paul V in Rome. While Sotelo was in Rome, the Pope appointed him as bishop of Oshu (Northern Honshu, the main island where Edo and Sendai are located). While this diplomatic mission was in Europe, Christiany was officially banned from all of Japan by a decree on January 27, 1614, and the executions of Kirishitans drastically increased. News of these executions reached Europe, and dashed the hopes of a trade agreement because the King of Spain refused to trade with a country that executed Christians. Many of the new Japanese Christian converts in the diplomatic mission chose to stay in Madrid rather than return to face death in Japan, and their descendants are still living in Madrid today. With trepidation the remaining members of the mission embarked on their journey back to Japan via Mexico and stopped in the Philippines where they stayed for about two years. Hasekura finally returned to Japan in 1620 after an absence of seven years, and his arrival was apparently big news in Japan and alarmed the Shogun who in turn ordered Date Masamune to stamp out Christianity in his domain. Date had warmly welcomed Hasekura and his delegation but quickly gave in to fear of the Shogun and distanced himself from the faith he had once embraced. Two days after Hasekura returned, an official order was put into effect in Sendai which condemned to death all Christians who would not renounce their faith, and which offered a reward to anyone who would turn in hidden Kirishitans, and which also ordered all missionaries to abandon their faith or leave Japan. Christian nobles would be exiled rather than executed. Forty days later, the first executions of Kirishitans in Sendai began. Hasekura was apparently not martyred at that time. Luis Sotelo had not returned from the Philippines to Japan with Hasekura because the Church authorities there did not want to send him back. Date even sent a ship to the Philippines to bring Sotelo back to Japan, but it was turned away without its intended passenger. After two years of waiting in the Philippines, Fr. Sotelo disguised himself as a merchant and secretly boarded a ship for Japan in 1622. But when he arrived in Nagasaki he was reported by the ship's Chinese captain and imprisoned in Nagasaki for two years. He was then burned at the stake in Nagasaki on August 24, 1624. Site 3.

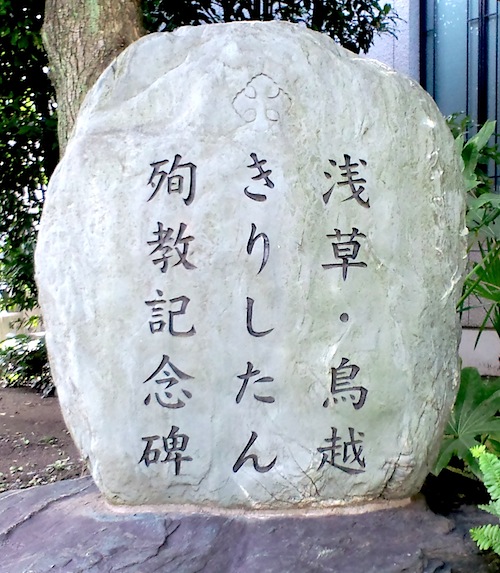

Among the buildings which now occupy this area is a Catholic church called Asakusa Catholic Church. It has a memorial dedicated to the Kirishitan martyrs who were executed at the Asakusa-Torigoe execution grounds which, according to one book I have read, was just to the northeast of this church, in the same neighborhood.  I went to visit this church on a national holiday and was dismayed to find that the gates were locked. The church is located on a small plot of land surrounded on all sides by sidewalks so I walked around to the back and discovered the memorial there, always open to the public.  The names of the twenty-seven martyrs mentioned above are recorded on this memorial. It says that in that area on August 16, 1613, among the group of prisoners taken from Kodenmacho prison to be beheaded were eight Kirishitan, and on the next day (August 17) fourteen more Kirishitans were executed, and on September 19 five more Kirishitan were executed. It mentions that one of these had just been baptized in the prison on September 19, and also lists the name of one more Kirishitan who had died in the prison, for a total of twenty-eight names.  Next to the plaque is a rounded stone that has an engraved cross and the following inscription in Japanese: Asakusa-Torigoe Kirishitan Martyrs Memorial.  Site 4.

Edo's notorious prison for nearly three centuries from 1596 till 1875 was located in Kodenmacho in central Edo near Nihonbashi. The grounds were surrounded on all four sides by a moat filled with water. The spot where it stood is now Jisshi Park. It's a small clearing with stones, gravel and trees typical of Tokyo inner city parks, and has a small pond. It's hidden by surrounding buildings but easy to find because it is right at Kodenmacho station. An elevator from the subway station actually opens at the park entrance where there is a large sign telling the story of this prison.  The prison was more of a stable than a prison and was itself often the cause of death for prisoners. It was so dark you could see nothing. Everyone sat on the floor, but there was no room to stretch your legs and you could only get to sleep by leaning on the person next to you. Most of the inmates were stripped down to a loincloth. There was no toilet, which meant the filth and stench would be overwhelming. When there was any kind of disturbance, the guards would pour buckets of human waste on everyone. And when prisoners died, their bodies were left in their position between fellow prisoners to rot for sometimes over a week. Most of what we know about this prison comes from the writing of Franciscan Priest Diego de San Francisco who actually spent a year and a half inside and lived to tell the story. Site 5.

Diego de San Francisco arrived in Japan in 1612 and was active in Evangelism in Kyoto. After the ban on Christianity in 1614 he continued his work secretly for another year until he was arrested in 1615 and thrown into the notorious Kodenmacho prison for a year and a half. Then he was released from prison and deported to Mexico in 1616. In 1618 he managed to enter Japan again and returned to Edo, this time disguised as a Japanese. He stayed for a time at the hospital for lepers near Asakusa where he ministered to the patients.

He stayed at the house of Kato's chief retainer, which became the base of his secret evangelistic activities. However, someone informed Kato, who investigated the affair and had his chief retainer beheaded. When he learned that Diego had previously stayed at the leper facility, Kato had all fifty resident patients arrested, and beheaded their leader. The compound of Kato Samanosuke Yoshiaki is now an office block (or blocks) near Uchisaiwai-Cho Station, across the large street from the Hibiya Kokusai building. An old history book I found in a library identified the buildings which stood on the exact site. I went to the area more than once trying to find those buildings and even asked the police officers at the local Koban (Police box) if they had any idea where the buildings might be. They had no idea. It turned out that those buildings have been torn down a long time ago and replaced by the one shown in the photo, called the Saiwai Building. If the former residence was really as big as a town, then the surrounding buildings also stand on the old property. I walked around and searched for some kind of marker or sign but there was none. The story is preserved only in old books. Site 6.

According to a book I have, the grounds were located somewhere in the vicinity of the intersection of Edo Dori (Avenue) and Kototoi Dori (Avenue) near the river. I went there and walked around but could not find a trace of the execution grounds anywhere near this bustling intersection. Today the area is dominated by the Tokyo Sky Tree across the Sumida River, which is the tallest tower in the world (as of this writing).

It seems incredible that there would be no indication of such a significant site in this area. I've gone back many times and have covered every street in the entire neighborhood, and haven't found any clues. My personal speculation is that the execution grounds are now a park called Hanakawado (or Hanagawado ) which is near this intersection just to the south west, and just a few blocks to the east of the Sensoji Temple grounds in Asakusa. The park has a small pond called Ubagaike which used to be much larger and was connected to the Sumida River nearby. I would imagine that access to flowing water would be a necessity since execution was a messy business.

The Japanese sign adds that the woman killed and robbed 999 men this way before killing herself in this pond, and that the events supposedly took place in the 6th century. Perhaps eleven-hundred years later the Tokugawa government saw it as a fitting place for executions since there was not much else they could build on a spot with such a reputation; nobody would want to build houses or businesses there as the Japanese tend to avoid all association with death! Just like the former site of Kodenmacho prison (above) where so many died, practically the only thing they could build on a site like this now is a public park. Here's a photo of the pond in the park.  I have visited this park several times, and it did have a spooky feeling, but that's not surprising considering my suspicions. One can imagine condemned criminals being lead down that walkway to the middle of the pond where the executioner was waiting. As for other likely candidates for the Asakusa-Yama execution grounds, this is the only park in the vicinity -- if you don't count the long park that runs along the Sumida River which was (and is) a popular spot for strolling and cherry blossom viewing and not a very wise choice for an execution spot. In addition to countless criminals, at least 231 Kirishitans were executed at the Asakusa-Yama execution grounds according to my source which also records how they were killed. The first executions were carried out by beheading as was the custom at the earlier execution grounds, but subsequent killings are described in my book with a Japanese term which can be translated as hanging upside down.

The Grand Inquisitor for the Tokugawa government was Inoue Masashige, whose title was Chikugo-no-kami (lord of Chikugo, a city in Kyushu). At least two sources said that Inoue was appointed to this post because he was in a homosexual relationship with Tokugawa Iemitsu who was the grandson of Tokugawa Ieyasu. According to one source, Inoue was also an ex-Kirishitan himself, and now it was his job to eradicate Christianity from Japan. He invented a cruel form of torture which was aimed at getting Kirishitans to renounce their faith. The victim was tied up and suspended upside down from the feet, with his head in a pit which was often filled with human waste. Some might still die in a few hours while others might remain that way for a few days -- unless they apostatized. Victims would be bound up with ropes very tightly, and to relieve the blood pressure on the head and prolong the agony, a gash was sometimes cut in the forehead to allow the blood to escape. This new cruel punishment was called "the pit" and was described as the worse form of torture imaginable. Site 7.

The next site is the location of the most famous Kirishitan martydom incident in Edo. It marked the beginning of the intense persecutions of the Church in Edo. In 1623, nineteen year old Tokugawa Iemitsu, grandson of Ieyasu, had just become the new Shogun in place of his father Hidetada. He immediately set out to destroy the Church. On December 4 of the same year, fifty Kirishitans were ordered to be executed. These included Jesuit Father Jerome de Angelis, Franciscan Father Francis Galvez, Japanese Jesuit Brother Simon Enpo, and Japanese layman John Hara Mondo.

During their time in the prison, the missionaries were held in separate parts of the prison, and each continued to boldly preach the gospel to their fellow prisoners day and night, with the result that many of the condemned criminals believed and converted to the Christian faith, and some were baptized right there in the prison (sprinkled with what scant drinking water was available).

The execution spot was to be outside the city gates to the south on a wooded hill called Fuda No Tsuji which faced the sea. It was on the Tokaido, which was the main highway running through Japan and which was always filled with travelers.  The Kirishitan prisoners were made to parade from Kodenmacho prison through the streets of Edo all the way to the city limits and on to the top of the hill. Judging by my map of Tokyo, they must have walked about seven kilometers (over four miles). The prisoners were divided into three groups. The two priests plus Hara Mondo were made to ride on horseback. Fr. Jerome de Angelis rode at the front of the first group, Fr. Francis Galvez rode at the front of the second group, and Hara Mondo rode at the front of the last group. The tendons of Hara Mondo's hands and feet had been severed in a previous arrest, and he could not walk. He could not even stay balanced on a horse by himself, so he was secured to the horse's back by ropes. His nose had also been cut off and a cross branded on his forehead.

The execution had been announced in advance so that there was a large crowd waiting around this hill and a neighboring hill as well. The method of execution this time would be burning at the stake rather than beheading or hanging in the pit. Fifty living human beings screaming as they were engulfed in flames on this hill by the Tokaido would surely make a lasting impression on the public. As it turned out, the impression made was not what they had planned on. Much of the description that follows is derived from a written eyewitness account of the event. When they reached the site, they saw fifty stakes prepared, with three of them set apart in the area closest to the city. Each prisoner was tied to a stake except for the three on horseback who were made to stay on their horses for the time being so they could witness the execution of the others. From their positions above the crowds the missionaries continued to preach boldly to all who could hear.

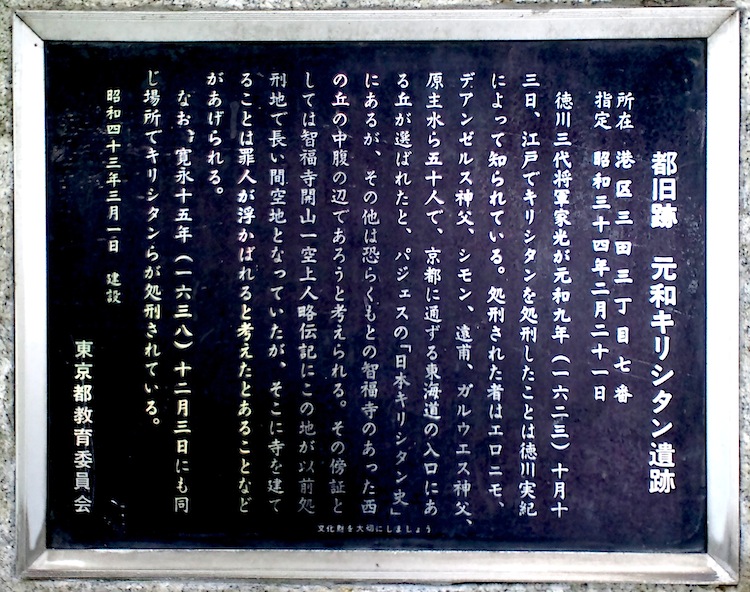

As the flames rose, none of the martyrs showed any sign of pain. Instead they all showed great courage and even joy as they offered up praise to God, to the amazement of the great crowd who recognized that this could not be possible by human efforts alone. As a matter of fact, a man and a woman rushed out of the crowd and shouted loudly to the guards that they, too, were Kirishitans and deserved to be executed. They were however, arrested and imprisoned instead. They would be executed later -- on this same spot. After the first group of believers had all perished and the fires had died out, the three leaders were taken off their horses and tied to the stakes. They continued to encourage each other and proclaim their faith in Christ. Fr. Jerome prayed for the city and then faced the flames directly and spoke to the crowds who were watching him closely. Finally he fell to his knees and died. John Hara Mondo encircled the flames with his arms as if embracing them, and remained fixed in this position the entire time as the flames burned him until he finally fell forward in death. Fr. Calvez lasted longest of the three, and remained standing, leaning on his stake even after he had died. Their charred bodies were intentionally left lying in the field as a warning to all, with guards posted to make sure that people could not steal remains (some managed to take some anyway). The second mass execution at Fuda No Tsuji in 1623 Three weeks later, on December 25 (one source says it was December 29), a group of 37 prisoners including the wives and children of the first group of martyrs were led out from the same prison to this hill. Also in this group were the man and woman who proclaimed their faith on this very hill three weeks earlier. Thirteen people in this group were not even Kirishitans but were apparently associated with them in some way. It was a crime to help Kirishitans or harbor them or even rent rooms to them. There were around 18 children, including some who were so young that they probably did not appreciate the gravity of the situation, and happily went along with their mothers, clutching their toys, a sight which moved many of the onlookers to tears. Some of these children were beheaded, others were slashed from head to navel, or sawn or even torn in pieces by the executioners as their mothers watched. Later their heads were hung from their dead mothers' hands. The method of killing this time varied. Eleven of the adults were then tied to crosses and run through with spears, and six others were burned at the stake. The man who had previously declared his faith at the first executions was named Francis Kahyoe. Now as the flames rose about him, Francis preached boldly to the crowd about faith in Christ as the only way of salvation.  At the top of that hill, a large stone, a pillar and a plaque on a smaller rock are the only reminders of these dark and evil events. The sign says that Kirishitans were executed by order of Tokugawa Iemitsu, and gives the names of the men who were leaders in the first executions on December 4, which I have mentioned above. It also mentions that more Kirishitans were executed here on December 30, 1638. I don't know if this is a reference to the second mass execution I mention above (with different dates) or a different execution. Most likely they continued to use this hill for occasional executions once it had been set aside for that purpose since it would be difficult to use it for anything else. Like other execution sites in Tokyo, this eventually became a public park.  These two mass executions were the beginning of a wave of persecution under Tokugawa Iemitsu. Over the next several years, two thousand Kirishitans would be martyred in Edo.

The closest train stations are Tamachi Station and Mita Station. Fumi-e and hidden Kirishitans

As part of its aggressive campaign to find these hidden Kirishitans, the Tokugawa government required all citizens to be registered as members of their local Buddhist temple. They also held public rituals called e-bumi on a regular basis where everyone was ordered to put their foot on fumi-e which were Christian images usually made of bronze depicting Christ or Mary. The two terms e-bumi and fumi-e are actually the combination of the same two Japanese words in different order, e means image and fumi means step or trample on. This system was introduced in 1629 and continued until Februay 12, 1858. Anyone who refused to step on the fumi-e was put to death. Many Kirishitans went bravely to their deaths this way, preferring martyrdom over the shame of abandoning their faith. However, some Kirishitans complied and stepped on the images while secretly holding onto the faith they had publicly renounced. Indeed, some local officials even encouraged them to just lightly touch their foot to the image in order to spare their lives. The rite of contrition took on a new prominence among secret Kirishitans as a way of dealing with the guilt. These photos show several fumi-e which are on display in a special Kirishitan exhibition which can be seen at least once a year at the Tokyo National Museum. The faces on most of these are worn smooth from being tramped on by many feet.

Locking down the entire nation In the late 1630s Tokugawa Iemitsu instituted a number of laws which isolated Japan from the world. This isolation was known as sakoku (locked nation) and was possible because Japan is an island nation surrounded entirely by sea. During this period no foreigner was allowed to enter Japan and no Japanese was allowed to leave on penalty of death. This effectively wiped out foreign missionary activity in Japan, and any Japanese who had become Christians during their time in a foreign country could not return to Japan. Japan became a locked and isolated nation and would remain this way for around 250 years. However, there were still some attempts by missionaries to secretly enter Japan. Peter Kibe Fr. Peter Kasui Kibe was a Japanese Kirishitan seminarian who had been expelled from Japan in 1614. During his years outside of Japan he made his way to Rome, walking much of the way! He made a stop at the Holy Land, becoming the first Japanese ever to enter Jerusalem. He then went on to Rome where he was further trained, and was ordained a Jesuit priest in 1620. He returned to Japan knowing he would most likely be martyred there. He landed in Kagoshima, and managed to make his way to the Tohoku region in northeast Japan where he worked with the Kirishitans there. On March 17, 1639 he was captured in Tohoku along with two other Jesuit priests, Giovanni Battista Porro and Martinho Shikimi, and two Franciscan Friars. The two Franciscans were burned at the stake in Shinagawa,

These new prisoners were such a big catch that even the Shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu himself was present to observe some of the questioning sessions. A special inquisitor called Chuan was brought in to pursuade the three Jesuits to apostatize. Chuan was none other than Cristovao Ferreira, the former Jesuit priest who had apostatized six years prior in 1633 while in the pit. Now he was working for the Japanese government and living in his own home in Nagasaki. He had been forced to take a Japanese wife, the widow of an executed Chinese merchant, and go by a Japanese name, Sawano Chuan. This interrogation failed to produce results, and apparently Peter Kibe used the occasion to encourage Ferreira to return to the faith. So Iemitsu took charge and had his specialist Inoue Masashige interrogate the three Jesuits with the goal of getting them to apostatize. This dragged on for ten more days. When it did not succeed, Inoue ordered them to be taken to the pit. The torture was very effective, and the two companions renounced their faith even as Peter Kibe continued to encourage them to resist. The two were apparently released from torture, but what became of them is not known. Peter Kibe, however, remained steadfast in his faith and continued to endure the torture until the guards finally got angry and killed him. Some accounts say he was run through with a spear, some say he was killed by applying red hot steel to his body, and yet others say he was disembowelled.

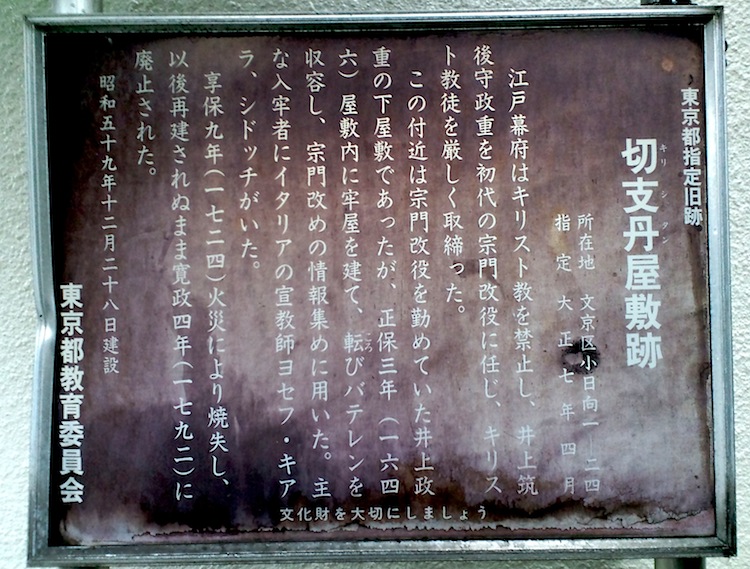

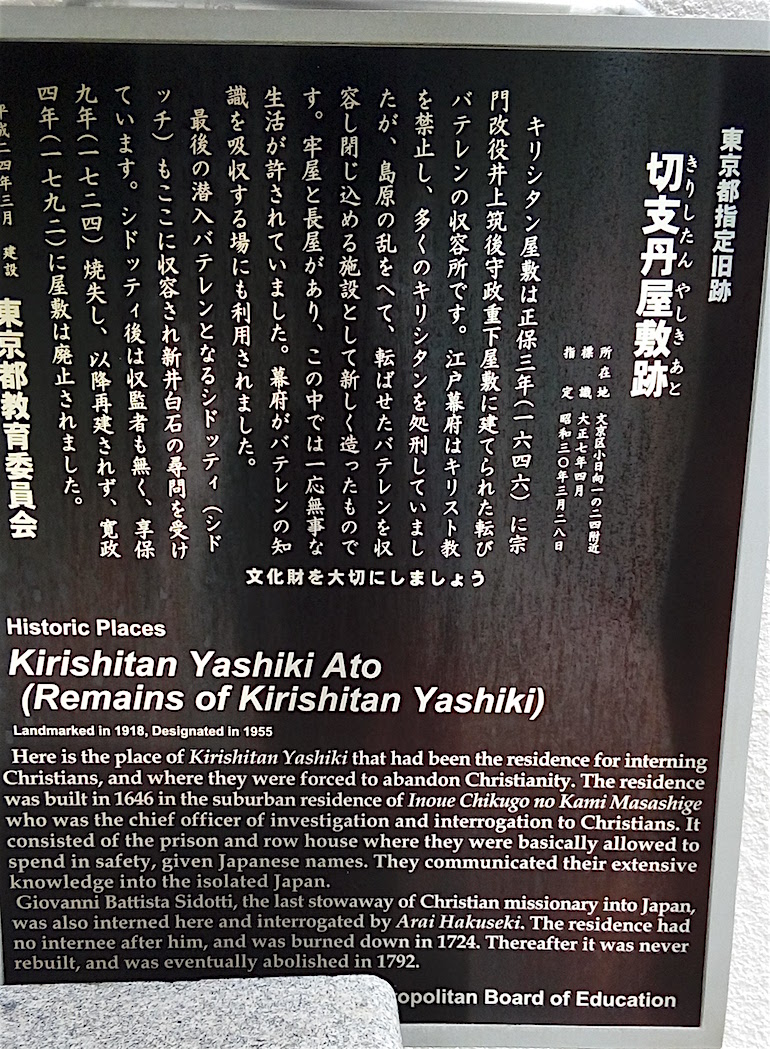

The Tokugawa government recognized the possibility of more missionaries infiltrating Japan at various remote locations, so a central compound was built in Edo where captured missionaries could be brought in from all parts of the country. The compound was called Koishikawa-Rogoku (Koishikawa Prison) and was at that time in an isolated area in Edo. The place is better known today as Kirishitan Yashiki (translated into English as Christian Compound or Christian Mansion) and is located in what is now a neighborhood not far from Myogadani Station.

Inside this area, a separate walled-in prison compound was built in the north part in 1646 for interrogating Kirishitans, and many were executed there. I went to this area and wandered around the neighborhood where Kirishitan Yashiki once existed, and found that not a trace remains of the former compound. There is a street on a steep incline with a tunnel at the bottom (runs under the Marunouchi train/subway line) which is identified on the maps as Kirishitan-zaka (Christian Slope) but there are no signs or markers on the street itself.  Kirishitan-zaka as seen from the top. The tunnel can be seen at the far end. During the Edo era this street was inside the compound and ran from the gate at the bottom of the hill (corresponding to the entrance of the current tunnel) to the residence of Inoue Masashige which was located in the area directly behind me as I took this photograph. The entire road was inside the walls of the compound and served as the only road leading in. At that time it was lined with trees and had guarded gates at both the lower and upper ends. The first missionaries in the Kirishitan Yashiki Kirishitans could be imprisoned and executed in this compound, and it also served as a place to house foreign missionaries who had apostatized. Among its first occupants were four Italian Jesuits Giuseppe Chiara, Pedro Marquez, Alfonso Arroyo and Francisco Cassola who had infiltrated Japan on a mission to find Cristovao Ferreira and convince him to return to the faith. They landed on the island of Oshima and wore Japanese clothes in hopes of going undetected. However, the locals noticed that their facial features were not Japanese, and reported them to the authorities. They were arrested in 1643 and taken to Hakata on the south island of Kyushu. Then they were moved to Nagasaki where Marquez was subject to water torture, There were several types of water torture in use including forcing the victim to swallow great amounts of water with a funnel and then beating his belly with bamboo rods. Apparently Marquez did not die from this torture, and all four were taken to Edo where they were interrogated by the government officials and even Tokugawa Iemitsu himself. Once again Cristovao Ferreira was brought up from Nagasaki to be the interpreter for these proceedings. This was ironic considering the sole reason they came to Japan was to find him. The four were then taken to the prison in Kodenmacho and condemned to the pit where they all renounced their faith under torture. They were then allowed to live in Japan under confinement, and given Japanese names. Giuseppe Chiara's last name was changed to Okamoto, and he was given a Japanese wife. They were later moved to the newly built Kirishitan Yashiki to live out their days in solitude. Apparently they were the first missionaries to live there. Nothing more is known of the fate of three of the men, but we know that Chiara remained at the Kirishitan Yashiki until his death forty years later in 1685. Before he died, he stated that he was still a Christian. The main character Sebastiao Rodrigues in the Novel Silence by Shusaku Endo was based on Giuseppe Chiara. In the novel Rodrigues comes to Japan in search of Cristovao Ferreira. The book has also been made into a Japanese movie in 1971, and more recently in 2016 directed by Martin Scorsese. The Scorsese movie is well worth seeing. Although it is based on a fictional work, it is faithful to historical details, including replicas of some of the fumi-e shown in the above photos. The story also features several real-life characters such as Grand Inquisitor Inoue Masashige and apostate missionary Cristovao Ferreira (played by Liam Neeson). Site 9.

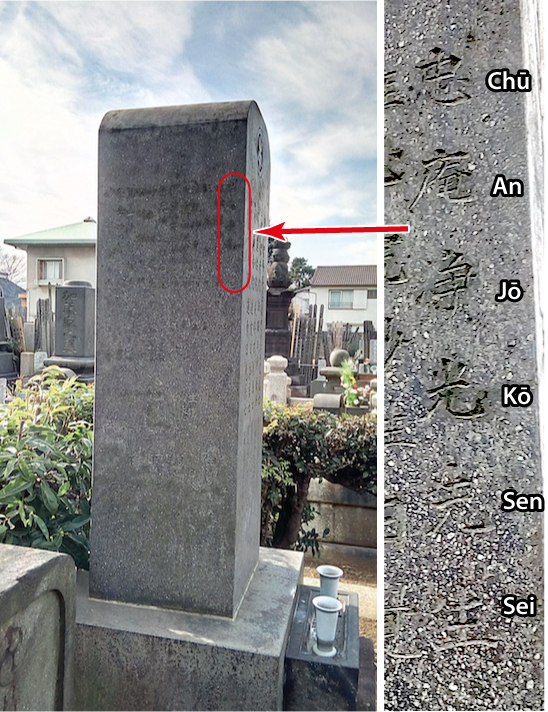

As for the fate of the real Cristovao Ferreira, apparently some Portugese and Chinese merchants who had met him in Japan spread the news that he had told them that he had regretted his apostasy and still held onto his faith and even carried a rosary with him. One report says that he was an old man in his eighties in Nagasaki when he began to loudly declare his Christian faith in public, which resulted in his being sent again to the pit where he died a martyr on November 4th or 5th, 1650. His remains were brought to Edo (Tokyo) and buried on the grounds of Motoyama Jiunzanzuirin Temple in the family plot of his son-in-law Sugimoto Chukei. Sugimoto had married one of Ferreira's daughters and moved to Edo where he was a personal physician of the Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune. Cristovao Ferreira's Japanese name Chuan with the title Joko Sensei can be clearly seen engraved on the stone even today. I have added Roman characters to the photo to identify the kanji.  It is a bit difficult to find the temple, and nearly impossible to find this particular stone among the many hundreds of grave stones surrounding the temple. After I entered the cemetery, I went to one corner and proceeded to walk among the stones hoping to stumble upon the right one, but gave up on that idea after about ten minutes. I went back to the entrance and prayed for divine help to locate the stone. Then I entered the cemetery again, took a few steps, looked around, saw the stone in the distance and walked straight to it in about ten seconds! I have provided instructions on a separate web page for any viewer who wants to find this stone in the future: Kirishitan Sites in Tokyo: The Grave site of Cristovao Ferreira which includes a map and photos and instructions on how to get there. The last missionary in the Kirishitan Yashiki The last missionary to live at the Kirishitan Yashiki was Sicilian Jesuit priest, Fr. Giovanni Battista Sidotti, who has also been called the "last missionary" to Japan. Since Japan was officially closed to the world, and it was illegal for missionaries to enter, Sidotti had to gain special permission from Pope Clement XI to go to Japan. He arrived dressed in native Japanese costume at Yakushima Island in Kagoshima, but was immediately spotted and arrested on October 11, 1708 and whisked to Nagasaki. Then he was taken to the Kirishitan Yashiki which had been standing for 62 years in Edo by this time. He was not able to send any message back to Europe, and it appeared as if he had simply vanished. Nearly two centuries would pass before anybody in Europe learned of what had happened to Sidotti.

Although these books were written in 1714, the inclusion of banned religious content kept them from being published until after the ban was lifted in the late 1800s. However, they were widely circulated in Japan in hand-copied manuscript form until then. The author of these books was Japanese government official and Confucian scholar Arai Hakuseki who was also an advisor to the Shogun at the time, Tokugawa Ienobu. Arai Hakuseki had interrogated Sidotti and came to have great respect for him, and Sidotti respected Arai as well. They subsequently had many conversations in which Sidotti passed on much valuable information about the western world. Sidotti also insisted that the Japanese government had been misinformed about the western missionaries and that they were not trying to open the way for foreign armies to invade. Arai Hakuseki advised the Tokugawa government to no longer torture or kill foreign missionaries as had been the usual treatment in the past, but to simply deport or imprison them, reserving execution as a last resort for extreme cases. So Sidotti was placed in confinement at the Kirishitan Yashiki without being forced to deny his faith. In his case it was more like a house arrest, and he was not treated like a prisoner. Since he was isolated from the outside world, he did not have any further opportunities to evangelize, and was thus spared further punishment -- until he tried to convince the elderly couple -- identified by their names Chosuke and Haru -- who were in charge of the residence that they should return to the Christian faith which they themselves had abandoned some time earlier. He succeeded and even went as far as baptising them, which resulted in his being moved to an underground cell despite a petition from Arai Hakuseki to show lenience. Giovanni Battista Sidotti remained in this state and died of starvation on November 27, 1714 at the age of 46. The Kirishitan Yashiki burned down seven years later. Giovanni Battista Sidotti had brought with him from Europe a painting of the Virgin Mary, which is now occasionally on display at the Tokyo National Museum in Ueno. It is similar to several paintings in Europe entitled "Our Lady of Sorrows" or "Our Lady of the Finger" because one finger is conspicuously visible. In Japanese it is called oyayubi no seibozo which could be translated, "image of the Holy Mother of the thumb" and is officially called "Madonna of the Thumb" on the Museum's web site when their Kirishitan exhibition is periodically announced. This painting is usually the centerpiece of that exhibition. It has been erroneously translated elsewhere on the web as "thumb-sized image of Virgin Mary" but I have seen this painting with my own eyes many times, This painting which depicts a sorrowful Mary with tears on her cheek is a fitting memorial to such a tragic part of Japan's history. The death of Giovanni Battista Sidotti at the Kirishitan Yashiki brought down the curtain on an era of missionary activity which had begun with Francis Xavier 165 years before. With the remaining Kirishitan faithful going underground, and no more foreign missionaries arriving in Japan, a period of silence ensued which lasted until the 19th century.  There is an old memorial not far from the Kirishitan-zaka. It has a pillar on the right side an old stone marker in the center with faint writing inscribed on it, and over the stone marker is a signboard erected by the local government with information which I have already written here. It mentions Inoue Masahige as well as Giuseppe Chiara and Giovanni Battista Sidotti, and says that the place burned down in 1724. There also a few other small stone memorials on the left.  A few years after I took the above photo, the sign was replaced by a new one that includes an explanation in English (photo below) perhaps to accomodate the increase in the number of foreign visitors to this spot. Maybe those visitors learned of the existence of the Kirishitan Yashiki from this article?  The old stone marker in the center is unreadable because it is so old and worn. I crouched in front of it for a while trying to figure out how At that moment a man walked by and stopped to see what I was doing. I greeted him, and we got into a conversation about the memorial and the stone with the faint script, and he went over to a mailbox which was on the wall behind the memorial to the left and pulled out a plastic folder full of papers (it only looked like a mailbox; it was actually a storage box, and you can see it behind the tree in the photo). Apparently somebody had already invested the time and energy to figure out what was engraved on the stone, and had printed up copies for visitors. The man gave me a copy which I scanned for this article. It basically gives the same information I have covered here (except in Japanese, of course). The remains Giovanni Battista Sidotti discovered Tokyo continues to change at an incredible pace, and no neighborhood is exempt, not even the old neighborhood which stands on the site of the old Kirishitan Yashiki. When it was announced that a new condominum complex would be built here, the neighbors protested and put up signs demanding the halt of construction plans. This is not necessarily a Christian neighborhood, but the residents did not want any further "desecration" of this historically significant area. The protests went unheeded as such protests always are, and the construction work began. As they were digging the land that would become a parking lot, human remains were discovered in April 2014. Objects and earthenware discovered at the site indicate that the remains were from the time period when Sidotti was imprisoned at the Kirishitan Yashiki. An investigation ensued, and two years later it was announced that the DNA from the skeleton was that of Giovanni Battista Sidotti.  The remains of Giovanni Battista Sidotti - Copyright Bunkyo Ward (BUNKYO WARD/AFP) The DNA is apparently of an Italian man who was over 170 cm tall. According to old records, Sidotti was from 175 cm to 178 cm tall (the height of the average Japanese man at the time was around 156 cm). As was the case with the excavated Christian remains near Tokyo Station described above, this body had not been cremated or buried according to the Japanese custom but laid out horizontally in a casket according to Christian practice. Judging from the metal brackets, the casket was apparently a luxurious one, which would seem inappropriate for a prisoner.

The only other Italian males known to have come to the Kirishitan Yashiki were the four missionaries mentioned above: Giuseppe Chiara, Pedro Marquez, Alfonso Arroyo and Francisco Cassola. The fate of three of the men is unknown, but we know that Chiara remained at the Kirishitan Yashiki until he died at the age of 84, and his body was cremated (this scene is depicted in the 2016 movie Silence where the main character -- based on Giuseppe Chiara -- is cremated in an upright sitting position in a wooden barrel-type container). The skeleton at the construction site was not cremated, and was of someone closer to Sidotti's age when he died at the age of 46. Based on the skull and recorded descriptions of Sidotti, the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo proceeded to create a replica of his head, and put it on display. Now it is part of the Kirishitan exhibition which goes on display at least once a year at the Tokyo National Museum

After Sidotti's bones were unearthed at the construction site, they were transferred to St. Mary's Cathedral in Tokyo -- or so I have read in several news articles in English. The Catholic Cathedral in Tokyo is the most obvious choice for the government to contact when Kirishitan remains are discovered here. However, when I went to the Cathedral to inquire, the man in the reception office there told me that Sidotti was definitely not buried at the Cathedral, and he had no idea where Sidotti's remains are today. This leads me to speculate that the remains are not buried at the cathedral, but perhaps are in storage somewhere in custody of the Cathedral until it is decided what to do with them. I did read in one article something to the effect that if a request came from Europe for the remains that they could be sent back. This would imply that they are not permanently interred at this point. I can't find any information about the couple's remains, but I would hope they were also transferred to the Cathedral or at least given a Christian burial somewhere else. Incidentally, the Cathedral also has a bone fragment of Francis Xavier. You can see it in the center of a medallion on the chest of a bust of Xavier in a display case near the entrance.

So the period of missionary activity which began with Francis Xavier's arrival in Kagoshima in 1549 came to an end with the death of Giovanni Battista Sidotti 165 years later in Edo (Tokyo) in 1714. Reopening the nation

Attempts by various nations to establish trade relations with Japan were repeatedly repelled -- sometimes with force. On July 8, 1853, four United States Navy warships (the famous Black Ships) under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry arrived at Uraga harbor near the mouth of Edo Bay (now called Tokyo Bay) with a letter from the President of the United States Millard Fillmore requesting a trade agreement between Japan and the U.S.A. These ships were huge, black and ominous, with clouds of coal smoke billowing into the air, unlike Japanese sailing vessels.

This demonstration of firepower shocked Japan whose own military technology had not advanced during the centuries of isolation, and made it clear that they had no choice but to let Perry's ships sail wherever they wanted, and to receive the letter. Perry said he would return later for a reply, and sailed on to China. After he left, the Japanese built fortifications in Edo Bay as a defense against a future American attack. But when Commodore Perry returned to Japan seven months later, he had twice as many ships with him. So rather than try to engage him in battle, the Tokugawa government signed a treaty with the United States granting all their demands.

Other western nations quickly followed in the wake, securing their own trade agreements with Japan. This led to the end of sakoku and opened the way for foreigners -- including Christians -- to once again enter Japan. New churches are built in Japan

(Partly due to this, Yokohama grew and is now is the second largest city in Japan by population, after Tokyo.) The first church to be built in Japan after sakoku had ended was Sacred Heart Cathedral, in Yokohama. It was built by the Paris Foreign Missions Society in 1862. Of course, the Japanese government made it clear that Christianity was still illegal in Japan, and that Christian worship activities must be restricted to foreign residents only. That particular church building was destroyed by an earthquake in 1923 and rebuilt at another location. Today a statue of Christ marks the spot of the original church building. It is located to the left of Exit 3 at Motomachi-Chukagai station on the Minato Mirai Line. Discovery of Kirishitan descendants and a new wave of persecution During the 16th century, Nagasaki on the southern island of Kyushu was the city most closely associated with Christianity in Japan. At one point the percentage of Kirishitans among the residents of Nagasaki was said to have actually reached 100 percent, and it was called the Rome of Japan.

The most well-known incident was the crucifixion of twenty six martyrs on Nishizaka (west slope) in 1597. According to the written records, over six hundred Kirishitans were eventually executed on this hill. The Kirishitan population of Nagasaki soon vanished. Many were killed while others renounced their faith. Still others became secret "hidden" Kirishitans (kakure Kirishitan) who pretended to abandon their Christian faith, and would step on the fumi-e but repent in secret year after year, as described above . The continued existence of Kirishitans in Japan for all those years was unknown to the Japanese government, let alone the rest of the world. But the area around Nagasaki and the surrounding islands were full of hidden Kirishitans who continued to worship and pass down the faith and traditions from one generation to the next for the next two hundred years. Among the Kirishitan traditions was a prophecy that the black robed priests who had brought the Catholic faith to Japan would return in great black ships after seven generations (if a generation is counted as around twenty to thirty years, this would come out to anywhere from 140 to 210 years). Another Kirishitan tradition was that the believers would recognize the true priests based on three criteria: the priests would have a devotion to Mary, they would be celibate, and they would be faithful to the Pope. When after over 220 years as a closed nation Japan was forced to open its doors to foreigners, an amazing incident occured in Nagasaki.

One of the priests in charge at the Church was Fr. Bernard Petitjean of the Paris Foreign Missions Society which had also built the first church in Yokohama (described above) a few years earlier.

To his surprise they asked him in Japanese to show them the statue of Santa Maria. They followed him through the dark church sanctuary to an area in the back where they could see the statue of Mary wearing a crown and holding the baby Jesus in her arms. Then they knelt down to pray.

Then they asked Fr. Petijean what was the name of the Great Priest who was the Grand Head of the Kingdom of Rome to which Fr. Petijean answered that it was Pope Pius IX, and that the pope would be happy to hear of their interest. Then they asked him if he had any children, and he replied that his children were these believers and their brethren, and that he must remain unmarried all his life. Hearing this, the small group bowed low and cried out their thanks to God. The prophecy had been fulfilled: the black ships had arrived, the black-robed priests had returned, and they had a devotion to Mary, were celibate, and were faithful to the Pope. This church building is still standing in Nagasaki, but I could not get a photo of the statue because photography is not permitted inside the church. The photo to the left was sent to me by Ralph Peter Goerlach, a researcher and author of a book on Kirishitans who received special permission to take photos.

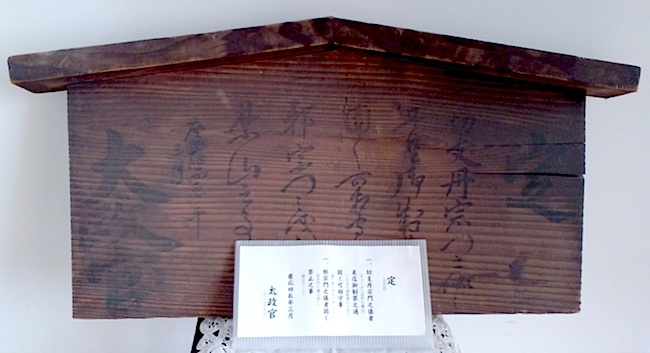

Many visiting Christians were happy to make the acquaintance of Japanese believers, and no doubt assisted them in various ways, and apparently gave them presents such as crosses, medals and rosaries. Unfortunately, all the well-meaning attention given by foreign visitors to the Kirishitans led to a new wave of persecution as Christianity was still banned, and even possessing such items was illegal. To the right is a European wood and brass rosary which was seized by the Japanese authorities from Kirishitans during the 19th Century. It's part of a special Kirishitan exhibition which can be seen at least once a year at the Tokyo National Museum. This one has a St. Ignatius Loyola medal (founder of the Jesuits, and Francis Xavier's mentor) and a Miraculous Medal attached to it (enlarged in the inset) as well as a Miraculous Medal center piece. During this time of persecution, thousands of Japanese Kirishitans were arrested, and their possessions seized. Then they were then exiled to different parts of Japan where their lives were ruined. The western nations condemned this persecution and pressured Japan to be tolerant of Christianity. Then came the Boshin War in 1868 which was a Japanese civil war fought mainly over the issue of the government's inability to withstand foreign pressure. This war lasted a year and a half and resulted in the downfall of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the formation of a new government under the rule of Emperor Meiji. The imperial government welcomed the assistance of other nations in its efforts to quickly modernize. However, they continued to enforce the ban on Christianity which was left over from the old regime. Finally on February 24, 1873, the signboards which had been posted throughout Japan banning Christianity for 250 years were quietly taken down by the new government in its fifth year, signaling official tolerance of Christianity and Christian evangelism in Japan.  One of the original signboards, now on display at Honjo Catholic Church in Tokyo It turns out that there were around 50,000 Kirishitans in existence at this time, and roughly half of them were open to instruction and correction so they could join the Catholic Church of their ancestors. What a joyful occasion that must have been for them. Many men from the Kirishitan community went on to become Catholic priests. Others in Kirishitan communities were unwilling to join the Catholic Church because they preferred their own traditions which had morphed into a mixture of Christianity and local religions. All the same, these Kirishitans enjoyed a friendly relationship with the Catholic Church and even participated in joint worship services, but their numbers have dwindled until now there are very few -- if any -- practitioners left. The Church returns to Tokyo (formerly called Edo) We must now go back a few years to see what was going on in Tokyo during this time. Although the Paris Foreign Missions Society had built a Church for foreign residents in Yokohama in 1862, and another church in Nagasaki in 1864, foreigners were still forbidden to even live in Tokyo until 1869. This was the year after the Tokugawa Shogunate had fallen, the Boshin War had ended, and the imperial government was established. The emperor had moved from Kyoto to Edo which was now called Tokyo (which means eastern capital). Foreigners were finally permitted to live in an area of Tokyo called Akashi-Cho which is in the east part of Tokyo now known as the Tsukiji area. Two years later, in 1871, the Paris Foreign Missions Society sent Fr. Marie Jean-Marie and Fr. Midon Felix from Yokohama to Tokyo, and they set up a small makeshift chapel in rented quarters in Inaribashi which was also in the Tsukiji area. Although the chapel was supposed to be for foreign residents because of ban on Christianity, most of the visitors were Japanese students, many from outside of Tokyo. The following year in 1872, these missionaries established a language school in Tokyo which taught French, German, English and Latin. This school was actually a Latin seminary to train Japanese young men to become Catholic priests. Around seventy students were enrolled at the seminary. The ban on Christianity would not be lifted until the following year, but the missionaries anticipated such a move and prepared for it.

Tokyo (Edo) had been without a church for 261 years since Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada destroyed ROZARIO NO GENKOU SEI MARIA SEIDO (Church of Queen Holy Mary of the Rosary) in 1612 or 1613, which incidentally had been built in the same general area as this new chapel. A few months after this new chapel was built, in the same year 1874, these missionaries established a second chapel to the north-west in the Kanda area (now central Tokyo). This second chapel was dedicated to Saint Francis Xavier, and the first chaplain was Fr. Alfred Pettier. This chapel would later become Kanda Catholic Church, the second Catholic Church in Tokyo after the ban was lifted. Kanda Catholic Church contains a relic of Saint Francis Xavier, a bone fragment. It is also my home church. Incidentally I had the privilege of meeting some relatives of Fr. Alfred Pettier when they came to Japan and visited Kanda Church. These are the oldest two Catholic churches in Tokyo, and both have served as Tokyo's Cathedral for a time. Tsukiji Catholic Church would be Tokyo's first Cathedral from 1877 to 1920. The first bishop in Tokyo was Mgr. Pierre Marie Osouf. Kanda Catholic Church which would become the Cathedral for the ten years following the Second World War. The current Cathedral in Tokyo is Sekiguchi Church also known as St. Mary's Cathedral. You can see a photo of the Cathedral above, in the section which talks about the remains of Giovanni Battista Sidotti. Lost years As I ponder the stories of Kirishitan martyrs in Edo and throughout Japan, I can't help but recall what Tertullian wrote in the second century, The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church. The hundred years between 1549 and 1650 are called the Christian Century in Japan. It is said that around 6.3 percent of the Japanese population was Christian during that time and the Church continued to grow at an amazing rate until it was stopped by force. During the 261 years from the ban on Christianity in 1612 until the time the ban was lifted in 1873, some 50,000 Kirishitans were killed. Today the Christians in Japan make up less than one percent of the population. There is no longer any fear of persecution and the Church in Japan has the freedom to grow from that seed planted by the martyrs. Yet it has not been able to flourish and grow as it did before those lost centuries. I pray that the Church in Japan will be able to rebuild on those old foundation stones in the power of the Holy Spirit, and with one voice proclaim the good news of Jesus Christ to every person in this nation, and exceed the hopes and expectations of those honored martyrs who gave everything for the Kingdom of God. Final comments: As a Protestant Evangelical Christian living in Japan since 1987, I was accustomed to hearing the stories of various Protestant denominations which typically began with missionaries who came in response to General MacArthur's call after World War 2, or perhaps as early as the Meiji era nearly 150 years ago. I came here as an Episcopalian, proud of the long history of the Episcopal Church in Japan which could be traced all the way back to its first two missionaries Rev. John Liggins and Rev. Channing Moore Williams who arrived here in 1859. Then I walked into a Catholic church in Tokyo and read about their history in Japan which began with the arrival of Francis Xavier in 1549. Eventually, my continuing study of the Bible and Church history led me to become a member of the Catholic Church. I hope this article will reflect some of my joy and excitement -- and gratitude for finally discovering this amazing treasure. Here is a list of some names mentioned above in their Japanese form. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

For further reading

There seem to be very few English language books on Kirishitan history. Most of my information came from library books published in Japanese (and for the record, it's still a challenge for me to read Japanese books). Here are some of the English language books which I have discovered:

Related Links

|

1 Some researchers claim that Syrian Nestorian Christians had reached Japan many centuries before Francis Xavier. But even if that is true, there were apparently no Christians in Japan when Xavier arrived. |

| |