|

Several ways to sing the Psalms

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contents:

The book of Psalms (Tehillim in Hebrew) was the prayer book of the Israelites in their synagogue worship. There are recorded instances in the Bible where Jesus took His words directly from the Psalms -- he even used the Psalms when he cried out in agony on the cross. And later when Jesus appeared to John on the Island of Patmos and told him what to write to the Churches, he still quoted the Psalms! Many of the Psalms are prayers which we can offer to God. Other Psalms tell us about God and His mighty acts. So we pray some Psalms and reflect on others. The Psalms are a conversation between God and His people. And when we read aloud those Psalms that talk about God, we join God in proclaiming His word to all who are around us, whether visible or invisible. Martin Luther said this about the psalter, which is another name for the book of Psalms: The psalter ought to be a precious and beloved book, if for no other reason than this: it promises Christ's death and Resurrection so clearly--and pictures His kingdom and the conditions and nature of all Christendom--that it might well be called a little Bible. The preface to the Tehillim by the Kehot Publication Society has this quote from Tezmach Tzedek, the third Lubavitcher Rebbe: If one would only know the power of the verses of Tehillim, and their effect on high, one would recite them continuously. The verses of Tehillim transcend all barriers and ascend higher and higher, imploring the Master of the Universe until they achieve results in kindness and mercy. Pope Benedict XVI has said that the Book of Psalms can teach people how to pray and is the prayer book par excellence: These inspired songs teach us how to speak to God, expressing ourselves and the whole range of our human experience with words that God himself has given us. Praying the Psalms can bring amazing results within you and in the world around you. It can help you and your family in times of disaster (see Psalm 91: God's Umbrella of Protection

Some psalters are arranged to be read through entirely once a week (and twice a week during Lent). Some monastics pray the entire psalter -- all 150 Psalms -- every day! A daily dosage of Psalms -- even only one Psalm a day -- might sound a bit tedious. That is, unless you sing them. The Psalms were intended to be sung. You may have noticed little notes to the chief musician or choir director at the beginning of some Psalms. In 1 Chronicles 29:31 we read of King Hezekiah ordering the Levites to sing the Psalms, and apparently they already knew the tunes because they just jumped right in and started singing: Moreover Hezekiah the king and the princes commanded the Levites to sing praise unto the Lord with the words of David, and of Asaph the seer. And they sang praises with gladness, and they bowed their heads and worshipped. The book of Psalms is a song book. Try reading through a book of your favorite songs without singing them and see how dry they are, like cornflakes without milk. Sing the Psalms, and you will find how gratifying it is, and you will look forward to doing it again. There are very few clues, and no musical notes in our English Bibles to help us sing the Psalms, but today there are several ways to sing them. This page describes a few good ways that I've discovered, and I'm sure there are more ways out there which I have not yet discovered. When I first wrote this article in 2010, the title was Three Ways to Sing the Psalms. But over the years people have brought to my attention other great ways to sing or chant the Psalms, so I had to modify the article and change the title to Several Ways to Sing the Psalms. That's the great thing about articles published on the web; you can edit them and make them better as time goes on. Back to the top In order to sing the Psalms, one has to either edit the words to fit tunes, or create tunes to fit the words. Metrical Psalms are of the first type, words edited to fit tunes. A standard metrical Psalm is written in Common Meter which is 8.6.8.6. That means in a four line phrase, there will be eight syllables, then six syllables, then eight syllables, and then six syllables. Here are some familiar tunes in Common Meter:

This is just a fraction of what is out there. Do you see any favorite tunes in this list? Amazing Grace is beloved by many, including myself, but it can seem a bit short if you've got a good harmony going and don't want to stop. With a metrical psalter you can belt out Amazing Grace with gusto until the cows come home and never repeat a single verse. Actually, as one reader pointed out, Amazing Grace is the name of the poem written by John Newton in 1779, and that famous tune came fifty years later and was called New Britain. Several hymns in the list are probably the names of poems rather than tunes. One of my favorite Common Meter tunes is St. Flavian. Here it is in the key of F. Notice the heavy bar in the middle of each line. That tells you where to divide the text. As you can see, eight notes are followed by six in each line of music.  And here it is in mp3 form so you can hear it: st_flavian_f.mp3 Here are a few verses of Psalm 103 in Common Meter. Try singing these verses to St. Flavian or a few of the tunes listed above (note that "stirred" is two syllables instead of one, as in "stirr-ed" while "bestow'd (bestowed)" is pronounced with two syllables and not three):

If you had a psalter arranged in Common Meter, you could have a great time singing the Psalms to a variety of tunes. They are beautiful when sung well in rich four part harmony, a cappella (without instrumental accompaniment). There are lots recordings of metrical Psalms on YouTube, many which came from actual worship services. Great fun! There are also some amazing professionally recorded collections of Metric Psalms out there, including this one called Psalms In Harmony Of the several ways to sing Psalms covered in this article, the sound of metrical Psalms is probably the most familiar to our ears. The Psalm text above came from the Scottish Metrical Psalter of 1650 also called The Psalms of David in Metre. This work is considered to be a careful translation that is faithful to the original Hebrew text. Some parts are even a closer reflection of the original Hebrew than the prose Psalms found in the English Bible because subtle nuances of the Hebrew text were brought out where extra syllables were needed. Whether or not the Hebrew is strong in this psalter, the English is clearly a bit strained. Imagine the incredible amount of work that had to go into this to fit the words to meter and also make them rhyme! Still, it communicates the meaning just fine, and you may come to love it. The slightly unnatural English text of Psalm 23 (and the tune that always goes with it) in this psalter is well known and beloved by many:

Some churches sing metrical Psalms exclusively (no other hymns) which I personally think is a great idea. Why sing hymns written by people when you can sing the powerful Word of God -- especially since you have so many great tunes to choose from, and are free to create more tunes in any musical style? You can order a copy of The Psalms of David in Metre from the Trinitarian Bible Society. They also sell Bibles with these same metrical Psalms in the back (in addition to the regular Psalms in the Bible, of course). You can also order it through Amazon. Here is another edition of the same metrical psalter plus a few other metrical psalters at Amazon:

Some of these have the older form of English which I love, being a fan of the Authorized King James Version of the Bible, but the majority of books listed here are in modern English. Back to the top The other way to sing Psalms is to keep the words in their original form, and create tunes to fit the words. Of course, this could result in 150 different tunes with complex and unpredictable melodies. Fortunately there is another option: chanting. Chanting is sort of a combination of speaking and singing. This is the key to singing text without rearranging it; most of the words are spoken in a monotone on the same note, and a small part of the text is sung to specific notes and rhythms, giving the chant its musical quality. One very old form of chanting is called plainsong, which has been around since the early centuries of the Christian Church, if not earlier. It is possible that parts of plainsong chants we have today came from the synagogue chants which were familiar to Jesus. Plainsong is also called Plainchant. Gregorian Chant is a form of plainsong.

Plainsong is especially suited to individual prayer since there are no harmonies or instrumental accompaniment, and the range of notes is relatively narrow and within the range of the average person. You can determine how high or low the chant will be sung, so no chant is ever outside your singing range. The music for plainsong chant (also called plainchant) comes from nine different basic tunes called Psalm Tones, and there are variations within these nine Psalm tones. In a plainsong psalter, the text is marked (pointed) to give the reader clues as to how to fit the words to the music. Each psalter has its own system of pointing, but they all follow the same basic principles. Here is Psalm tone II (Psalm tones are usually identified by a Roman numeral) with pointed text from Psalm 103:8. In Do RE MI terms, the first note in this example is FA, but it has so few notes, you can consider it DO if that makes it easier.  An asterisk marks the division between the first and second section, and corresponds to the bar in the center of the music. In some psalters a colon is used instead of an asterisk for this. Slashes further divide these sections into two parts. The first part corresponds to the long bar in the music, and all the words before the slash are sung on one note. The second part after the slash is very short, and corresponds to the notes in the music; each syllable gets its own note. Plainsong was originally written in a form of music notation known as neums, which are the ancestors of modern music notation. Some plainsong psalters still use neums while others use modern notation. Here is the same chant in neums (and in this example the first note really is DO on the DO RE Mi scale):  There are a few other elements of plainsong which aren't covered here, but if you have grasped this much, then you'll have no problem with the rest.

If you use a plainsong psalter regularly, you will soon have a collection of Psalm chants in your head at your disposal so that even when you open the Psalms in your Bible, you will be able to sing them naturally because the chants will pop into your head. The Plainsong Psalter of 1932 mentioned above is nearly impossible to find, but Lancelot Andrewes Press came to the rescue by producing Saint Dunstan's Plainsong Psalter

While the 1932 Plainsong Psalter was written in modern musical notation, this psalter is done in the original square neum notation which is really much easier to sight read because it is less cluttered. Like the 1932 Plainsong Psalter, the Psalms in the Saint Dunstan's Plainsong Psalter are the Coverdale Psalms. This is an excellent work, and fills a great need. You can get a copy from Lancelot Andrewes Press or Amazon Here is a web site with recordings of various Psalms chanted from The Saint Dunstan's Plainsong Psalter, chanted by Brother Benedict, OSB of St. Augustine Orthodox Church in Denver. Also, recordings of The Compline Service at St. Mark's Cathedral usually include chanting of the Psalms in beautiful Plainsong by a men's choir. The layout of Saint Dunstan's Plainsong Psalter has each page with the music notation at the top, followed by the text of the Psalms, which means you sometimes have to figure out which syllable falls on which notes, and in my case it's often a judgement call when there is more than one possibility.

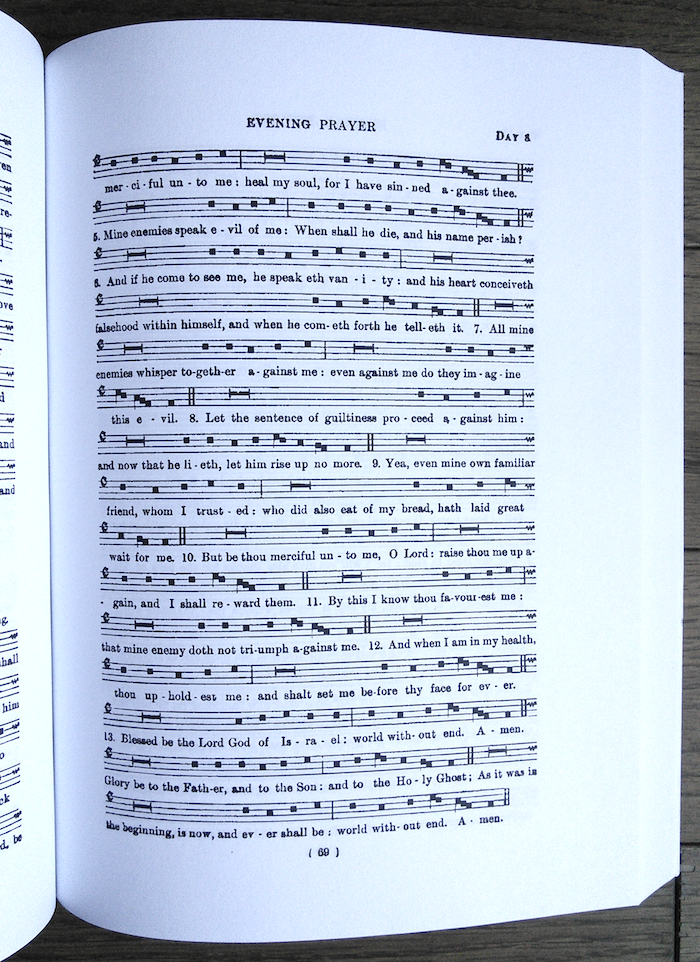

You can find a facsimile e-book in Google Books for free. Just get a Google account, and do a search from within Google Books. In that that edition, you use one Psalm tone for all the Psalms in each day's Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, which keeps it all simple, if not a little monotonous. An entirely new edition was published in 1902 by H.B. Briggs and W.H. Frere under the superintendence of John Stainer. That edition uses a different Psalm tone for each Psalm. A facsimile can be found on the web and it can be downloaded in various formats for free. I first downloaded the Kindle and epub versions, but found them useless because the text from the page images was simply converted into e-book format, which resulted in a mess of characters.So I downloaded the PDF version which preserves the images of each page. Fortunately a print version is also available from Amazon in both paperback I bought the paperback version (photo on the right). This is apparently a "print on demand" book because the printing date on the last page was the same day I ordered the book. How do they do that? Amazing! It's a fairly big book at 7.5 X 10 inches, and nearly an inch thick (19 X 25.5 cm, and nearly 2.5 cm thick). I prefer small books for my prayer time, but sometimes we have little choice but to go with "big book devotions" because of limited options. But it's very easy to use if you set it on your lap, and takes all the guesswork out of chanting in Plainsong so you can think a little more about the words (my constant battle). As you can see below, it almost has to be a large book for readability, and the printing is very crisp and clear.  The Manual of Plainsong is available in yet one more form which is very nice, and must have taken a lot of work to create: David Stone of Cambridge, U.K. has produced an amazing collection of PDF files of The Manual of Plainsong which you can print out. These are not scanned images of the original book, but newly created pages based on the original book, so they are clean and crisp and enlarge and print very well. Of course, these are much lighter files than the scanned facsimile editions on the web, and they also look much better in your tablet. Specking of praying with a tablet, if you use iBreviary, you may want to see my separate article called How to chant the Liturgy of the Hours with Gregorian Chant -- on iBreviary. Here are a few other plainsong related materials at Amazon:

A simple improvised plainsong type of chant If you don't want to find a plainsong psalter, here is a very simple and versatile chant that will serve as a springboard for improvisation. The first note is written as C, but that is only to show how the other notes relate to it. Simply think of it as DO on the DO RE MI scale, and sing it as high or low as you want.  The long square bar is for singing the majority of the words on one note in a natural reading style. Then you change the note of the final syllable or syllables as indicated in the music: go up a note at the end of the first line and drop down two notes at the end of the second line. Different words break at different places. For example in Psalm 93 (below) the word "majesty" would require an accent on the first syllable but not the final two syllables. If such a word occurs at the end of the first line, go up a note on "ma" and drop back down to the original note for "jesty" (I put this "dropping back down" in parentheses in the music score since sometimes it is needed and sometimes it is not). On the second line, you have a choice, depending on what sounds most natural to your ears. You could drop down a note in the middle of "girded" as I have done, or somewhere else.

Most Psalms are divided into groupings of two lines each. The chant is therefore divided into two sections. If there are three lines grouped together instead of two, just repeat the notes of second measure for the final line.

(This is a departure from traditional Plainsong which would have you modify the tune for the first line instead of the last line, but with this improvised method, there is no need to plan ahead or backtrack when you suddenly discover you still have an extra line.) Note that the words "robed" and "moved" can also be split into two syllables if you are using the traditional way of pronounciation as in the word "wicked." This could result in a change in the melody:

There is no universal agreement on which words should be divided and where. Feel free to improvise and let the words divide naturally according to your own judgement. If you are singing by yourself to God, then there is no need to conform to established formulas. An even simpler form of chant is called recto tono which is Latin for straight tone. You simply recite the entire Psalm on one note! I once heard a guy behind me in church chanting a Psalm this way and thought he was simply being rebellious or displaying some kind of misguided piety. Now I realize he was chanting in a very old and acceptable form. Try it some time and you might warm up to it. It's probably the easiest form of chant to use with straight text versions of the Psalms; because your chant is on "automatic pilot" you don't have to think about the delivery and can focus more on the content of the Psalms. Back to the top Psalm Tones for English Psalms Plainsong (Gregorian or Plainchant) was originally created for the Psalms in Latin, and I have read that Plainsong is therefore a perfect and beautiful fit for Latin Psalms while there is some awkwardness and compromise when trying to chant English Psalms to these same Psalm tones. I have never studied Latin, but apparently it has something to do with the difference in the number of syllables and where the accent falls on them. If you are not satisfied with the various attempts to fit English Psalms to Latin Psalm tones, there are many original Psalm tones created for English text and based on the Gregorian modes. Among these are the St. Meinrad Psalm tones and the Conception Abbey Psalm tones. These are flexible tones which can be adapted to fit stanzas with two or more lines, and still sound dignified and natural. These Psalm tones are perfect for the Revised Grail Psalms which were published in 2010, and arrange the Psalms into stanzas of various numbers of lines. An excellent article called Chanting Universalis: Singing the Divine Office talks about these and even more options, and serves as a good starting point for further inquiry. It has several useful PDFs for download. There is also the very popular The Mundelein Psalter There are also the Psalm Tones by Fr. Samuel Weber, which are quite popular. You can read more about them at the New Liturgical Movement web site. The Revised Grail Psalms Singing Version does not contain musical notation, but accents are printed above the sentences, several per line, to cover every syllable which would be stressed in natural speaking. However, most Psalm tones focus only on the final accented syllable in a line, ignoring all the other accents. So all the work that went into finding every stressed syllable was not necessary. The Psalm Tones written by David Clayton take into consideration more accented syllables so the music comes even closer to the rhythm of natural speaking. You can hear samples at YouTube and can read more about them at his web site. The author of the article mentioned above (Chanting Universalis: Singing the Divine Office) brought these modern English Psalm tones to my attention, so I decided to do a little further digging on the web. And I liked what I discovered. I tried several of these Psalm tones, and fell in love with them. I have made a few resources to help me sing the Psalms to the St. Meinrad Psalm tones (some sound files and printable cards) which might be helpful for others, so I have linked them from a separate page called Some resources for singing the St. Meinrad Psalm Tones.

The Murray Tones are particularly popular and can be found on page 1716. I like these because there are eight tones corresponding to the eight Gregorian modes, just like the Saint Meinrad Psalm tones which I usually use. I have assigned a tone number to each Psalm which I have pencilled in my breviary next to each Psalm, so if I want to chant the Psalms with the Murray Tones, I can use the same number references. These tones are written in various keys, which can be a challenge for people who who have trouble reading music and are singing rather than playing a musical instrument. In my copy I have drawn little red arrows and circles to indicate which note is "DO" so I can jump right in and start chanting. Back to the top Another way of singing Psalms which conforms the music to the text is called Anglican Chant. This form of chant came from plainsong, and was created to allow Anglican church choirs to chant the Psalms in four part harmony. It first appeared around the same time as the first Book of Common Prayer in the 16th century, so apparently it was intended to be used with the psalter (produced by Miles Coverdale) in that prayer book. Plainsong at the time was in Latin while Anglican Chant was in English. By the way the Coverdale psalter is still widely used, and is printed in several prayer books as well as pointed psalters, both plainsong and Anglican Chant.

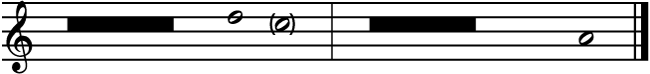

The original Anglican Chants were simple, and sounded like plainsong. But over the years, Anglican Chant has evolved into beautiful and complex pieces which are wonderful to hear when performed by a choir. If you search for "Anglican Chant" on You Tube you find some absolutely beautiful samples which will move you to tears. A lot of Anglican chants were intended to be sung by choirs in four part harmony, and therefore do not hold up well when sung by an individual. However, there are many simple Anglican chants with solid melodies which are great for chanting alone during your personal prayer time. Here is the melody (soprano) line of a classic Anglican chant that appears in many old psalters and hymn books. Below it are two lines from Psalm 103 of the Coverdale text with pointing as it appears in the Cathedral Psalter (in that particular psalter a different chant is used with this text). If you need help, the final note is DO on the DO RE MI scale:  Praise the Lord | O my | soul : and all that is within me | praise His | holy | Name. The upright bars in the text correspond to the bars in the music and the colon corresponds to the heavy bar (it's a good place to pause and take a breath). Usually the whole notes will contain more than one word -- even a string of words, while the half notes are assigned to one syllable each. You may feel tempted to rush through the string of words to get past it and on to the musical part, but just take your time and read the words naturally with feeling. The same goes for plainsong. Here I have colored the parts to show how they go together:  The great thing about Anglican Chants is that there is one standard pattern so any pointed Psalm will fit any Anglican chant. Here are a few books of pointed Psalms for Anglican Chants at Amazon: For those who have fallen in love with Anglican Chant, there are several CDs available, in addition to what you can find on You Tube. One is The Psalms of David If you want to hear ALL 150 Psalms, there is a 12-CD set:

Psalms of David Complete Of course, anything sung by a choir in a Cathedral with loud pipe organ and all those echoes is likely to be difficult to follow along, so my next quest was to find a pocket-size edition of the Coverdale Psalms so I could carry it with me and read the Psalms as I listened to the chants. I discovered that such a pocket-size edition of the Coverdale Psalms as they are sung in Anglican Chant does not exist anymore, except in a pocket-size Book of Common Prayer which is still available in an inexpensive hardbound edition There is a pocket size edition of the Coverdale Psalms called A Psalter for Prayer: Pocket Edition I did find one paperback edition of the Coverdale Psalms from the 1928 American Book of Common Prayer called The 1928 Prayer Book Psalter You can also find free copies of just the Coverdale Psalms at Google Books, where you can download them for free as e-books or PDFs so you can read them on your tablet or Kindle. Back to the top Chant in some Orthodox Churches Byzantine Chant is a form of chant used in some Orthodox Churches. They also arrange the music to fit the text. One way it differs from Plainsong and Anglican Chanting is that there is a lot more improvisation involved. The tone (or scale) of each chant is given, which determines the beginning, middle and end notes of each phrase (like a Plainsong Psalm tone)

I'm not familiar enough with it to say much more than this, but there is a Byzantine Chant workshop in podcast form on the web called Glory To Thee with a downloadable PDF text for you to start leaning this style. It can be found at Ancient Faith Radio. There are also forms of chant used in other Orthodox Churches which are different from Byzantine Chant, such as Common tones and Kievan tones. You can learn more about these at the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) web site in their article Tutorial for Learning the Tones. There are also Valaam tones. Here is a PDF which shows the eight Valaam tones. In the PDF, the red notes indicate the ison which is a note that another singer quietly holds while the main singer sings the main melody. Here's a YouTube video of Psalm 50 sung in Valaam Chant. Back to the top

The lyre appears many times in the Psalms. The two terms lyre and harp are often used interchangeably, but the lyre is more ancient and existed before the harp. The lyre was also smaller and more portable than a harp. David apparently carried around a lyre and played it as he watched over his sheep in the field. You also can accompany your Psalms on a 7 string lyre. The sheep are optional. These lyres use the ancient and universal pentatonic scale which has only five notes. All five notes sound great together no matter how you arrange them. Making music on a pentatonic scale comes naturally and intuitively. It allows you to pluck any string and make music without trying, and it makes a very relaxing and pleasant sound. As you play the same seven strings over and over again, you can discover your own set of Psalm tones. I have written more about using this lyre and the Pentatonic scale, and have even uploaded Pentatonic Psalm tones in a separate article called Singing the Psalms with a Seven String Lyre. I have also written an article called Singing the Psalms with a Ten String Lyre for those who prefer to not use the Pentatonic scale. Back to the top When you cannot use your voice In the 4th century Saint Augustine wrote about his mentor Bishop Ambrose of Milan and his amazing ability to read without using his voice. Apparently there was a time when nobody read silently or even considered it! But today, sometimes you have to share your devotional space with people who are doing other things, and vocal expression is not an option. You can still elevate your experience of the Psalms by saying them silently and deliberately. A lot of people move their lips when they read; it's not a big deal (unlike in Saint Augustine's time). One method which I have found very helpful in such situations is to take a breath before every phrase and say that phrase silently while exhaling. It helps you to focus, prevents you from drifting absent mindedly through large sections, and can be very rewarding. By the way, in noisy crowded places, ear plugs can make a world of difference in your ability to concentrate; in noisy crowded Tokyo, I use earplugs a lot. Having said all that, I still encourage you to sing or say the Psalms out loud when you can, even if it is so quiet that it can only be heard by yourself. If you are not getting much out of your devotional time, find a time and place where you can use your voice and see if it doesn't make a world of difference; it certainly does for me. If you pray a Psalm mentally, your mind can easily wander, but if you are using your voice, then the Psalm is entering your mind via your eyes and ears for double input. You might forget what you read but remember what you heard. I often use my voice when I'm walking and praying or reciting scripture, and I usually sing rather than just speak (setting scripture to music helps you to memorize and retain better, by the way). Lots of people sing to themselves when they are walking in public. It's funny actually; people who talk to themselves are considered odd and to be avoided, while people who sing to themselves are considered perfectly normal. Back to the top The dark side Just a word concerning some of the "darker" Psalms that ask God to punish our enemies. Remember that no living human being is beyond the transforming power of God's salvation, or can be written off as an enemy. Our true enemies are described in Ephesians 6:12: For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places. The contents of the Bible are in the context of the conflict between Good and evil which began before humans existed. These enemies assault all humans every day. Saint Padre Pio said, "If all the devils that are here were to take bodily form, they would blot out the light of the sun!" Any reference in the Psalms to an evil person or enemy can rightly point to Satan and the fallen angels who rebelled against God. You can keep these unseen enemies in mind as you call down God's judgement -- and pray for the salvation of their human agents. This will turn the Psalms into a manual for spiritual warfare as you direct these cursing Psalms to the evil one from whom all evil springs. Back to the top Make it your own One last thing: As you concentrate on singing the Psalms, it is easy to forget what is really important, namely to make the words of the Psalms your own. In 2 Samuel 24, King David wanted to build an altar and make an offering to the LORD at the threshing floor of Araunah (also known as Ornan in 1 Chronicles 21). Araunah offered to give David the oxen and wood and everything he needed so he could make the sacrifice. But David insisted on paying for them and making them his own before offering them to the LORD. Otherwise he would be offering something that was not his. When you open the Psalms and make a sacrifice of praise to the LORD, make them your own words. Otherwise you will be offering up somebody else's sacrifice. I struggle with this almost every day. I'll chant several verses, feel happy that I was successful in combining words with music, and then realize that the words went from the page to my mouth but somehow bypassed my mind. At those times I simply backtrack and chant the lost verses again. I like to think that this makes the devil really angry, who would rather not hear those Psalms chanted over again. Of course, some people don't let it bother them, and simply move on without doing it again, and that's fine, too, of course. As I've said before, the same Psalms will come around again in a few weeks anyway. Chanting the Psalms brings great blessings. As you make the words of the Psalms your own, you will be forced to conform your attitudes and thinking patterns to God's Word; it will transform you. You'll discover a thrill that you never knew was hidden in the Psalms. In your spirit you will perceive that God has been there with you as you prayed His words back to Him. Even if you were sleepy or tired or uncomfortable as you sang the Psalms and felt you didn't get much out of it, afterwards you may feel like the two men on the road to Emmaus who later realized that their hearts were burning within them simply because they were with Jesus. Your spirit will crave that experience again and again. That alone should be more than enough reason to want to try this!

|

|

| |

| If you click on any of the Amazon links and buy something there, a few pennies per dollar goes into my Amazon account. It's like a tip jar except the tip comes out of Amazon's pockets and not yours -- and it does not effect the price of the item. Of course, if you can find the same items at a Christian book shop, then by all means buy from them and help keep them in business. |